Episode 1. Welcome to Countermelody , or Claudia and Zazà

SOCIAL SHARE

SUBSCRIPTION PLATFORMS

SHOW NOTES

Hi, everyone, and welcome to the Show Notes page for Countermelody! Every week I will provide interesting ancillary material relevant to each individual podcast episode. Please come back here frequently to check out stuff designed to enhance your Countermelody experience.

RECORDINGS FEATURED ON THE EPISODE

A breakdown of the recordings used in this episode, accompanied by my brief expostulations and YouTube links where available.

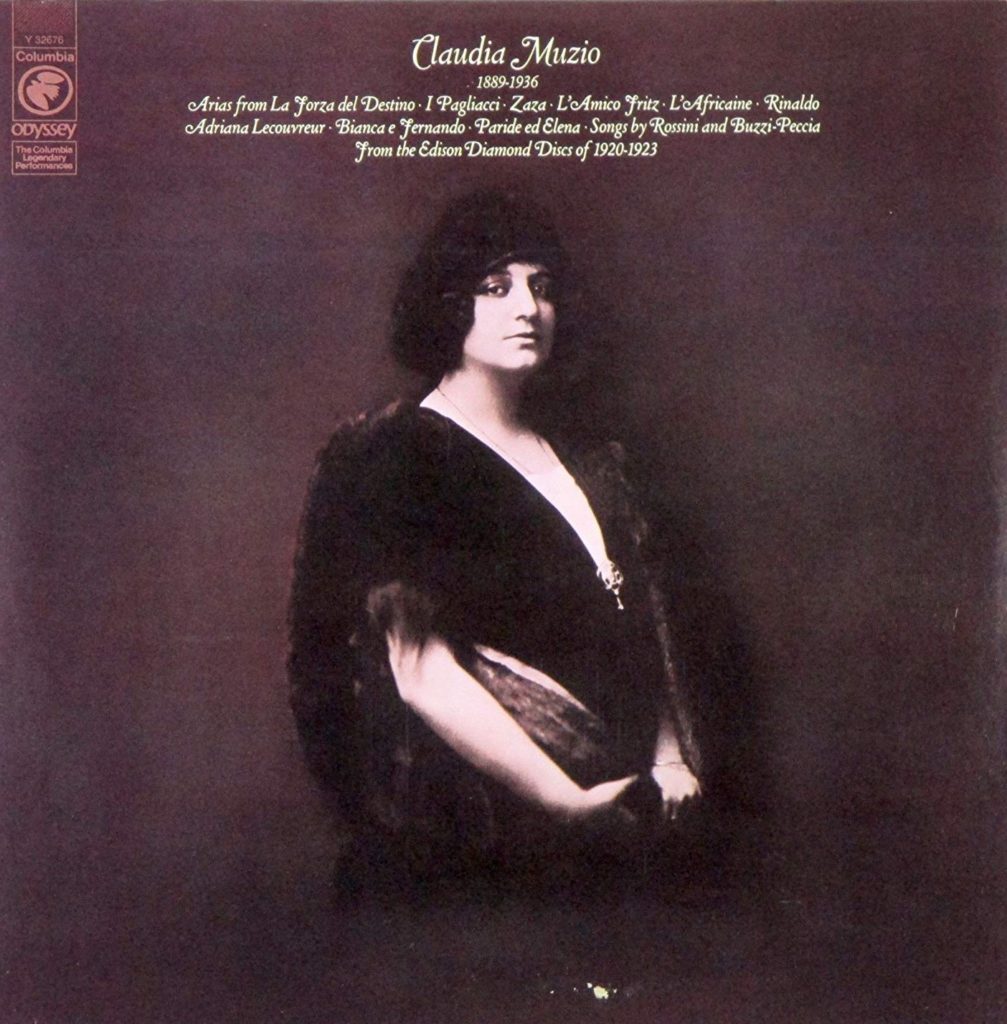

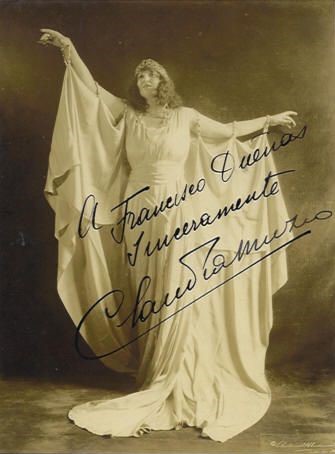

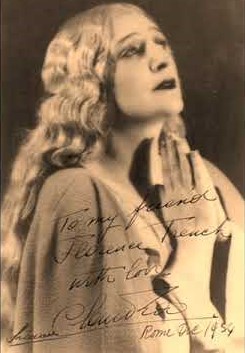

Licinio Refice (1883-1954): Per amor di Gesù [L’annuncio] (Cecilia). Claudia Muzio, Licinio Refice, conductor (Columbia BQX 2500, April 1934): I only use the orchestral introduction to this extraordinary recording in the podcast. This is from the prologue of his azione sacra. Before I dug a little deeper into this hybrid piece, I assumed that Refice, an ordained priest, had written the role for Muzio. But no! It was actually written with the soprano Maria Viscardi in mind, although in fact Muzio sang the world premiere in Rome as well as subsequent performances around the world, including in Buenos Aires and Montevideo. In the podcast, I refer to footage of Muzio and Refice arriving in the latter city; here is the link. About the aforementioned Maria Viscardi I have thus far discovered very, very little. Perhaps I’ll have more to report in a later episode.

Pietro Mascagni (1863-1945): Son pochi fiori (L’Amico Fritz). Claudia Muzio (Edison 82291, February 1923): This gem of an aria, from Mascagni’s second-most popular opera, is perfectly inflected by Muzio. , whose character here, Suzel, is a simple peasant girl whose parents are tenants of the wealthy landowner Fritz. Here she presents a birthday bouquet and greeting to the older Fritz, on whom she just might be nursing a secret crush. Interestingly, the singers in the premiere were Fernando De Lucia and Emma Calvé, who left some of the most fascinating and problematic early opera recordings in existence.

Alfred Bachelet (1864-1944): Chère nuit. Claudia Muzio (Edison 82218, November 1920): Alfred Bachelet (1864-1944), the composer of this song, written originally for Nellie Melba, was between 1907 and 1919 the principal conductor of the Paris Opéra. From there he served as the director of the Conservatoire in Nancy, a post he held until his death. Though he wrote some large-scale orchestral works and several operas, he is today remembered solely for this fragrant parlor song, which Muzio sings with a plangent sense of phrasing and excellent (though not quite flawless) French.

Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835): Sorgi, o padre (Bianca e Fernando). Claudia Muzio (Edison 82267, March 1922): The opera, Bellini’s first professionally-staged work, featured the tenor Rubini as Fernando and Méric-Lalande as Bianca (she also created the lead roles in La straniera, Il pirata, and Lucrezia Borgia). The famous bass Luigi Lablache was also in the original cast. Not a bad cast for your first professional production! As for this recording, Muzio never sounded better vocally than she does here; furthermore, her ability to extract every last drop of emotional sap from a vocal line, is on full display.

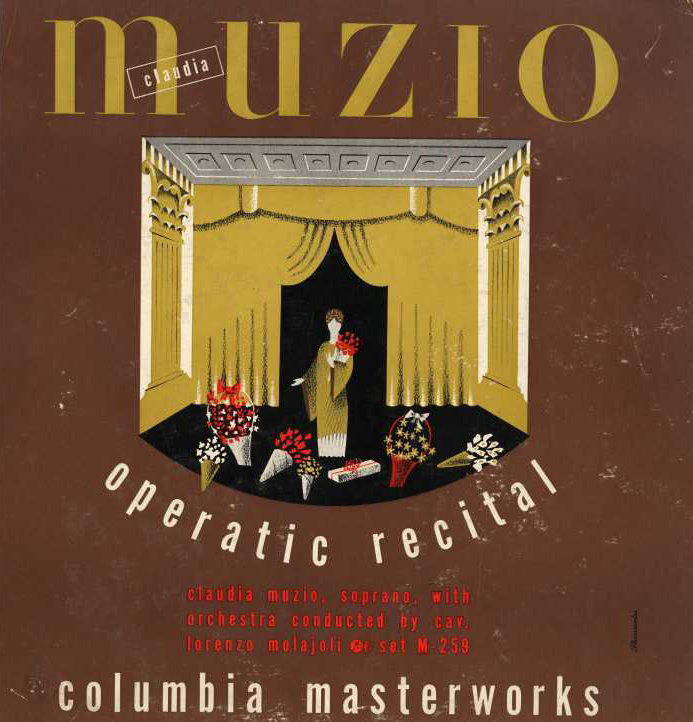

Arturo Buzzi-Peccia (1854-1943): Colombetta. Claudia Muzio, Lorenzo Molajoli, conductor (Columbia BQX 2501, April 1934): Arturo Buzzi-Peccia (1854-1943), was a voice teacher who trained, among others, Alma Gluck and who also composed a handful of songs. These were popular among opera singers looking for concert repertoire; his single opera, Forza d’Amore, though conducted by Toscanini at its 1897 Turin premiere, was not a success. Muzio recorded two of Buzzi-Peccia’s vocal bon bons, “Baciami” (which she also sang on a Metropolitan Opera Sunday Concert in 1920) and the charming “Colombetta,” in which she is at her most effervescent.

Léo Delibes (1836-1891): Bonjour, Suzon. Claudia Muzio, Lorenzo Molajoli, conductor (Columbia BQ 6000, June 1935): Muzio recorded this trifle of a song three times, twice for Edison (one of this in English as “Good Morning, Sue,”) and this late version. What I love about some of the late Muzio Columbias is how her playfulness and tenderness becomes somehow tinged with fatigue and sadness. Maybe a little like the late work of Judy Garland… IDK.

Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857-1919): Zazà, 1947 “nuova edizione” by Renzo Bianchi (excerpts from orchestral introductions to Acts III, II & IV). Orchestra Sinfonica di Torino della RAI, Alfredo Silipigni (RAI, September 1969) [no YouTube link]: As I describe in the podcast, the complete performance from which these excerpts are taken is in some ways extremely competent, even admirable, particularly the performance of Clara Petrella in the title role. And yet, the truncated version performed here does a real disservice to Leoncavallo, removing as it does many of the more charming and original aspects of his opera.

Licinio Refice (1883-1954): Ombra di nube. Claudia Muzio (Columbia BQX 2502, June 1935): A song that the composer of Cecilia composed for Muzio. She sings here of the longing for a day without dark clouds, commanding them to flee so that her torment can finally be appeased, allowing her to see into eternity. I know it’s dangerous to read too much into the way that a particular artist’s life might color the way that they approach a text, but I can’t help but think that Muzio understood all too well what she was singing about here.

Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857-1919): Dir che ci sono al mondo (Zazà ). Claudia Muzio (Edison 82243, November 8, 1920): This is discussed at length on the podcast, as well as played in its entirety.

FEATURED ARTISTS

I mention a slew of artists in this episode and I think it’s appropriate to provide a short description of some of them as well as examples of their work.

Eleonora Duse (1858-1924). While it is outside the scope of these pages to go into great depth about the great Italian actress, I do hope that those who are interested will delve a little deeper into the life, work, influence, and legacy of this extraordinary woman. For starters, her single film, Cenere [Ashes] (1916), can be viewed on YouTube in a dim and rather damaged print. Though Duse thought very little of the effort, it is still fascinating as the sole extant document of her acting, and plays upon the ever-popular trope of maternal sacrifice. Apparently a rather neglectful mother herself, Duse was romantically and/or professionally involved with some of the most important creative artists of her generation, including Arrigo Boito, Gabriele d’Annunzio, Isadora Duncan, Yvette Guilbert, and Eva Le Gallienne. She was particularly associated with the plays of Henrik Ibsen.

Rosa Raisa (1893-1963). Arrigo Boito: L’altra notte (Mefistofele). (Gennaro Papi, conductor; Vocalion 70036, recorded between 1920-23): One of Muzio’s fellow divas in Chicago was the great Polish-born, Italian-trained, Russian-Jewish soprano Rosa Raisa, née Raitza Burchstein, who was generally recognized in her day along with her fellow Rosa, Ponselle, as one of the supreme vocal artists of her day. Though she sang the title role in Norma in New York in 1920, her US career was primarily centered in Chicago, where she, along with Muzio, Garden (who served as director of both the Chicago Opera Association and the Chicago Civic Opera), Galli-Curci, and Edith Mason, reigned supreme. These days of course Raisa’s name is most closely associated with Puccini’s Turandot, which she created at La Scala in 1926. Sadly, broadcast recordings of both the Puccini premiere and many of her greatest Chicago assumptions were not preserved. When Marston Records issued Raisa’s complete recordings in 1998, aficionados were finally able to reevaluate this estimable singer, whose recordings until then had been considered spotty and unrepresentative of her best work. With Marston’s remasterings, one can finally form a clearer picture of Raisa’s importance as both a vocal phenomenon and an interpretive artist.

Mary Garden (1874-1967). Franco Alfano: Dio pietoso [in French] (Riseurrezione). (RCA Victor 6623B; 1926): The eccentric Scottish soprano created or was closely associated with early performances of a number of important French operas, including, most importantly, the female leads in Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande and Charpentier’s Louise. As noted above, she also served as the controversial director of two different manifestations of the opera companies in Chicago. Though she possessed a relatively modest vocal talent (certain vis-à-vis artists such as Raisa, Muzio, or Mason), she still sang a wide range of roles, including the title roles in Manon, Thaïs, La traviata, Le jongleur de Notre Dame, Carmen, Tosca, and Salome, the latter of which created a particular scandal when she sang it in its New York premiere in 1909. Though she made some historically important recordings with Debussy at the piano, I have always found these to be memorable mostly for the wrong reasons. But revisiting some of her other after a hiatus of many years, I found myself surprised at how viable the voice is. Since we are focusing on verismo work in this episode, it’s interesting to sample her excerpt from Franco Alfano’s Risurrezione, which she recorded in French as Dieu de grâce. Her modest voice fairly throbs with passion here; it’s a very effective rendition.

Daniel Gundlach. Franz Schubert: An die Musik . (livestream, July 2019): As I mention in this episode, this song, by my all-time favorite composer, almost got used as the podcast’s theme song. Perhaps if I were more of an egomaniac, you’d be hearing my performance of this at the top of every episode! At any rate, I performed a self-accompanied version in a recent livestream that I made for the supporters of my podcast.

Lotte Lehmann (1888-1976). Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Ich ging zu ihm (Das Wunder der Heliane). (Manfred Gurlitt, Berlin State Opera Orchestra, Odeon O-4812, March 1928): Depending on which day of the week it is, you will hear me proclaim either Muzio or the sublime Lotte Lehmann as my favorite singer of all time. There is an extraordinary recorded document of Lehmann, who shared the title role of Das Wunder der Heliane with the Austrian soprano Maria Hussa in the original 1927 production in Vienna. Her performance of the second act narrative, Ich ging zu ihm, is, in my opinion, the most erotically-charged bit of operatic singing I have ever heard, as well as a supreme example of Lehmann’s sheer vocal prowess, as well as her ability to shape and mold a complicated musical and dramatic scene. You may need to sit down for the end of this one.

Anita Cerquetti (1931-2014). Gaspare Spontini: O re dei cieli (Agnese di Hohenstaufen).(Arturo Basile, conductor; RAI, live December 1956): This is the first music I ever heard emanate from this venerated throat. Cerquetti is simply one of the most glorious dramatic soprano voices I have ever heard. Unusually, she was particularly well-suited to the music of Spontini and Cherubini, as well as the big bel canto and Verdi roles that are particularly difficult to cast. It was a short but brilliant career and rumors abound as to why that was the case. I will be devoting significant podcast time to this extraordinary artist.

Eidé Noréna (1884-1968). Giacomo Puccini: Tanto amore segreto… Tu che di gel sei cinta (Turandot). (Piero Coppola, conductor; HMV DA 4382, 1932): Noréna fascinates and inspires me. A singer who was only a modest success in her earlier career, she completely remade her small voice and technique and reemerged at the age of 40 to enjoy previously unknown success at the world’s greatest opera houses, the Opéra de Paris, in particular. With her compact but finely-tuned instrument she was able to sing roles ranging from Pamina to Blondchen to Ophélie to Violetta to Juliette to Liù to Desdemona to the Queen of Shemakha in Le Coq d’Or, always bringing an intensity and profound expressivity to her interpretations. She shares these traits with the wonderful Rumanian soprano Ileana Cotrubas, who was also able to assume rules that were perhaps a few sizes too big for her. Though she was Norwegian, I will certainly cover her in my series on great singers in the French style.

Florence Quartararo (1919-1994). George Frideric Handel: Care selve (Atalanta). (Jean Paul Morel, conductor, RCA Victor Orchestra; RCA 49-0549, 1949): I mention in the podcast that she possesses a similar vocal quality to Ponselle’s, though during her very short career she did not achieve the same heights that Ponselle did. Her brief marriage to the Italian bass Italo Tajo proved to be the unfortunate end of her career. Thankfully, her vocal gift is preserved in a smattering of live and studio recordings which prove her enormous versatility and range. The story is that Toscanini wanted her to appear as Desdemona in his broadcast of Otello, but that the Met, with which she was under contract, would not release her for rehearsals. A great loss for posterity, for sure. We remain grateful for what little remains for us to savor.

Rosa Ponselle (1897-1981). Hercule de Fontenailles: À l’aimé.(Romano Romani, piano; RCA 2053-A, October 1939): Amazingly, this recording, which is perhaps the greatest recorded example of a flawless blend of registers, was made in two years after Ponselle had withdrawn from her operatic career. It is a mere trifle of a piece, and yet it completely robs me of my breath when I listen to the way that this great singer negotiates the nearly two octaves of this song with complete ease and aplomb.

Hugo Hasslo (1911-1994). Jacques Offenbach: Scintille, diamant [in Swedish] (Les Contes d’Hoffmann). (Nils Grevilius, Stockholm Royal Orchestra, January 1946): Hugo Hasslo lived from 1911 until 1994. He made his debut in 1940 in Stockholm and remained an important member of the ensemble there for the duration of his career. He was particularly successful in the Italian repertoire. I came upon him entirely by accident when I purchased a CD in the Great Swedish Singers series on Bluebell Records entitled In Memoriam, clearly a memorial tribute. I was shocked by how good he was and wondered why I had never heard of him before. The primary reason, it appeared, was that, apart from a few guest engagements in Hamburg, London, and Edinburgh, his career was a so-called provincial one, centered as it was almost entirely in Sweden. Get a load of his singing of his 1946 recording, in Swedish, of Dappertutto’s aria known in French as “Scintille, diamant,” Never mind that Offenbach composed this aria for a completely different operetta, Le voyage dans la lune, and that it was first inserted into this opera 25 years after Offenbach’s death. Just listen to Hasslo let it rip and be glad for that indignity.

Heinrich Rehkemper (1894-1949). Franz Schubert: Die Nebensonnen (Winterreise). (Polydor 90019 A; 1928): It was my friend Gavin Carr who first introduced me to this singer. Though Art Song, and Lieder in particular, is one of my great loves, two of the most celebrated interpreters of Lieder are my particular bêtes noires. Since the focus of this podcast is on singers that I love, I will most likely never mention them by name on this podcast. Unfortunately the influence of both of those artists has been wide and deep. Rehkemper, on the other hand, falls completely outside of the influence of either of those artists. He is but one of a large number of Lieder interpreters who takes a completely different interpretive and vocal approach to this repertoire. There will be a major series on Lieder singing in the first season of Countermelody and I look forward to discussing the work of Rehkemper and many others with you then.

Gérard Souzay (1918-2004). Franz Schubert: Nacht und Träume. (Jacqueline Bonneau, piano; Decca LX 3104, April 1953): I intend to devote a full podcast to the French baritone, whose artistry continues to reveal itself to me in all its glory. He was by no means a flawless artist, and he experienced a major vocal and artistic decline in the mid- to late-seventies after which he was seldom listenable. But he sustained a long career and, like the “little girl who had a little curl right in the middle of her forehead… when [he] was good she was very, very good, and when [he] was bad…” Oh, you know what I mean. For now, let yourself be transported into the world of dreams. The way Souzay sings this song, I find myself calling out, as in the poem, “holde Träume, kehre wieder.” I hope you do, too.

Jorma Hynninen (b. 1941). Jean Sibelius: Norden. (Ralf Gothóni, piano; Finlandia FA 202, 1980): I know that Finland is not part of Scandinavia, but let’s just say that those Nordic countries have produced their share of great singers. Among those artists, I find Jorma Hynninen to be one of the greatest of all. His insight into art song, particularly Sibelius and Schubert, simply cannot be topped. It’s extraordinary that he continues, as he approached the age of 80, to still sing occasionally in public, and with a still fully-functional voice. This recording of Sibelius’s haunting Norden, accompanied by his frequent recital partner Ralf Gothóni is from his early prime. We’ll be spending time with him as well in future episodes. And no, as I have remarked before, my near-idolatry of him and Souzay has absolutely nothing to do with their extreme handsomeness. Perish the thought!

Giacomo Lauri-Volpi (1892-1979). Vincenzo Bellini: A te, o cara (I Puritani). (RCA Victor 7226, 1928): Lauri-Volpi was a close colleague and fervent supporter of Muzio. Depending on which account one reads, he either spearheaded or secretly provided the financing for Muzio’s last series of recordings, for Columbia in Rome, the ones on which her reputation primarily rests. In his 1955 book Voci parallele [Parallel Voices], published nearly twenty years after her death, he coined the oft-repeated description of Muzio’s voice: as “made of sighs and tears and restrained interior fire.” As can be heard in this excerpt, Lauri-Volpi himself was a technical paragon. It was he, in fact, who provided Franco Corelli with significant mid-career vocal guidance. Muzio undertook the title role of Puccini’s Turandot for a single outing in Buenos Aires in 1926, in which Lauri-Volpi was her Calaf, a role he undertook later the same season at the work’s Metropolitan Opera premiere. Here he provides a lesson in bel canto singing in the great aria from I Puritani.

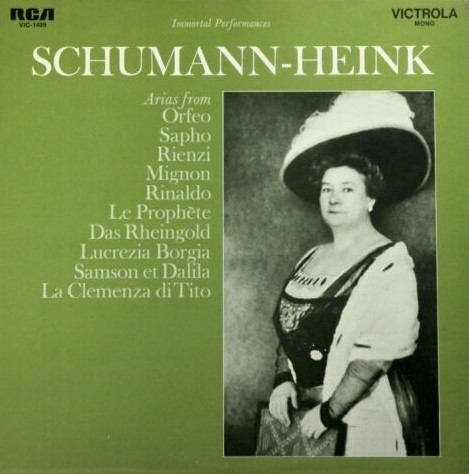

Ernestine Schumann-Heink (1861-1936). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Parto, parto (La Clemenza di Tito). (Victor 88196, September 1909). This was the first cut on that RCA Victrola record that I purchased at the St. Olaf College bookstore more than 30 years ago. While the voice of Mme. Schumann-Heink didn’t have the immediate impact on me that Muzio’s did, I remember being impressed, even at the time, by her long, sustained trill in the Mozart excerpt linked here. My grandmother would speak of hearing Mme. Schumann-Heink singing Stille Nacht on the radio during the holiday season. We’ll be doing a special holiday episode in December that will certainly feature that recording.

Eugenia Mantelli (1860-1926). Gioacchino Rossini: Una voce poco fa (Il Barbiere di Siviglia). (Zonophone I 6010, recorded between 1905-07): Though I only became aware of her with the Marston Records release featuring her complete recordings. She proves herself to be one of those now-extinct creatures, the coloratura contralto. There are a number of singers who have specialized in Rossini in recent years to great public success. I will make two confessions here, probably to the horror of many: first: I have a very low tolerance for Rossini’s comedies, Cenerentola partially excepted, and furthermore, though a number of contemporary singers have specialized in this repertoire, the singing of few if any of them is not much to my liking. Now, give me Mantelli or someone like Conchita Supervia (or even Teresa Berganza or Frederica von Stade in their primes) and I’ll be singing a completely different tune. Listen to the way Mantelli whips through those runs!

Sigrid Onégin (1889-1943). Giacomo Meyerbeer: O prêtres de Baal (Le Prophète). (Electrola DB 1290, 1929) Of all those rara aves, the coloratura contraltos, my very favorite is the extraordinary Swedish singer Sigrid Onégin. It’s extraordinary to think that at the time that Meyerbeer wrote the role of Fidès in Le Prophète, there were singers out there that could actually toss this repertoire off with ease. Wouldn’t it be magnificent if we could hear what Pauline Viardot sounded like in this role? At least we can hear the force of nature that is Onégin in this part.

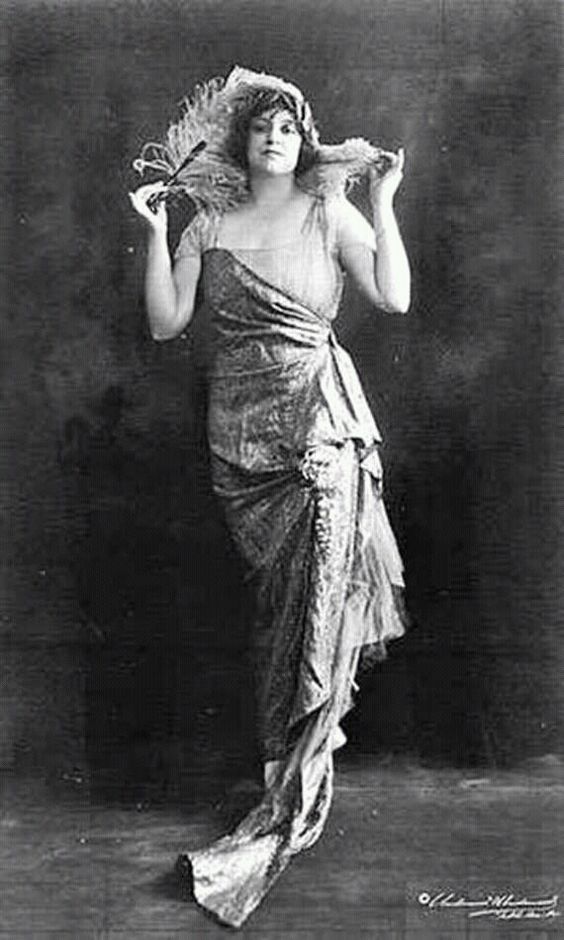

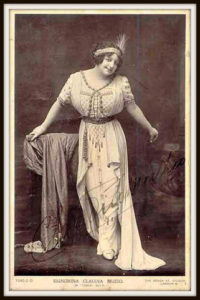

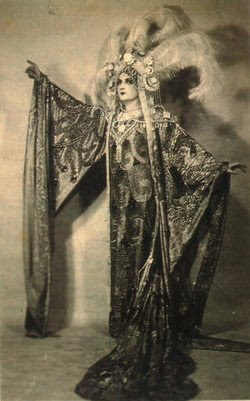

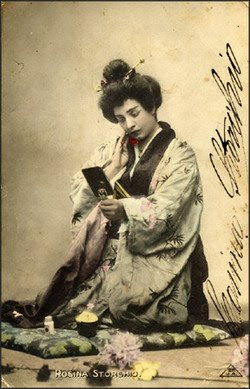

Rosina Storchio (1872-1945). Ruggero Leoncavallo: Mimi Pinson, la biondinetta (La Bohème). (Fonotipia 92861, 1911). Rosina Storchio created the title roles of Zazà and Madama Butterfly, so it’s rather puzzling to modern-day listeners to discover that her other roles included many of the so-called “-ina roles,” including Amina in Sonnambula and Norina in Don Pasquale. Other verismo roles that she created were the title role in Mascagni’s Lodoletta, Stephana in Giordano’s Siberia and Mimì in the other Bohème, that of Leoncavallo. Strangely the aria that she recorded from that opera, linked here, is actually assigned to the other lead female, Musetta, specified in the score as a primo mezzo soprano lirico. Rosina Storchio and Toscanini carried on a scandalous extramarital affair which resulted in the birth of a severely handicapped child who lived in enormous physical hardship until the age of sixteen. Storchio’s career lasted only four more years, after which she herself suffered from various afflictions until her death in 1945 at the age of 73.

Geraldine Farrar (1882-1867). See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

Eva von der Osten (1881-1936). See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

Wolfgang Windgassen (1914-1974). Johann Strauss II: Als flotter Geist (Der Zigeunerbaron) [live recording from the grounds of Bayreuth]. Windgassen is mentioned in the podcast as the nephew of the distinguished soprano Eva von der Osten. I had been previously unaware of this connection, remembering him primarily as the somewhat underpowered and overaged, yet still oddly compelling Siegfried on Solti’s pioneering Ring recording (and, even better, as Birgit Nilsson’s Isolde in the 1966 Bayreuth live recording of Tristan und Isolde). He is heard to best advantage, in my opinion, in the title role of Lohengrin in the live Bayreuth recording from 1953 conducted by Joseph Keilberth and also starring Eleanor Steber, Astrid Varney, and Hermann Uhde. Here he is heard in an rare outing from sometime probably in the late sixties behind the Festspielhaus at Bayreuth singing from Strauss’s Der Zigeunerbaron.

Emma Carelli (1877-1928). See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

Bidú Sayão (1902-1999). Giacomo Puccini: Un bel dì (Madama Butterfly) [The Voice of Firestone, telecast of 4 February 1952]. The diminutive Brazilian soprano was a favorite at the Met between 1937 and 1952. Because of her superb technique and ability to project her small but clear voice, she was able to undertake, as was the slightly older Noréna, a range of roles that might have been considered somewhat too large for her, including Violetta, Manon, and Juliette. Nevertheless, excepting for a sole outing as Margherita in Boito’s Mefistofele in San Francisco in 1952, just before her 50th birthday, after which she retired from opera, she resisted venturing into heavier repertoire, though Butterfly and Manon Lescaut remained a particular temptation. In the “-ina roles” and as Mozart’s Susanna, she was perfection. (Interestingly, her biography includes its own #MeToo moment: during a 1934 audition with Arturo Toscanini, after offering her a role in Giordano’s Il Re, he evidently attempted to employ the casting couch. She walked out of the audition and lost the part. Two years later, however, he conducted her in her US debut, in Debussy’s La Demoiselle Élue.)

Giuseppe Danise (1882-1963): See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

Clara Petrella (1914-1987). Giacomo Puccini: Sola, perduta, abbandonata (Manon Lescaut). (RAI 1956 film with Angelo Questa and the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano della RAI): Clara Petrella was one of those fearless, gutsy Italian sopranos whose singing almost always thrills me. According to her Wikipedia entry, she was also associated by her nickname (“the Duse of singers”) with the great Eleonora Duse. I don’t know anything about that, but if you watch the way she throws herself around in this excerpt from a 1956 film for Italian television of Manon Lescaut, you aren’t going to see a lot of subtlety, but you are going to get the extremely satisfying experience of seeing the soprano lip-sync to her earlier studio recording of the title role while throwing herself violently about the sand- and boulder-strewn stage set. (See also ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.)

Patricia Craig (b. 1947). See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

Aprile Millo (b. 1958). See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

Denia Mazzola Gavazzeni (b. 1953). See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

Mafalda Favero (1905-1981). See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

Giacinto Prandelli (1914-2010). See ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ.

in that extroardinary Adriana Lecouvreur in Napoli, November 1959

Magda Olivero (1910-2014) with Franco Corelli (1921-2003). Francesco Cilea: La mia fronte [final scene] (Adriana Lecouvreur). (Live performance on 28 November 1959; Mario Rossi conducting the Orchestra del Teatro di San Carlo di Napoli]. The great Italian verismo specialist died almost exactly five years ago at the age of 104. She had one of the longest and strangest careers in the history of opera. Possessed of a distinctive but curious-timbred voice, she turned a potential disadvantage into an incalculable advantage by finding every possible color therein and mining it for every last expressive possibility. She made a belated Met debut in 1975 at the age of 65 and gave her last performance on the operatic stage in 1981 in Poulenc’s La voix humaine, though she continued to give occasional live performances for years afterward. Her greatest role was Adriana Lecouvreur in Cilea’s eponymous opera, and the performance you hear was one in which the stars converged: she was called in at the last minute to replace an ailing Renata Tebaldi and gave the performance of her life opposite a cast the likes of which has rarely if ever been heard before: Franco Corelli, Giulietta Simionato, and Ettore Bastianini. By another miracle, the performance was recorded; it has been a major part of the ongoing Olivero legend ever since.

Renata Scotto (b. 1934). Giacomo Puccini: Senza mamma (Suor Angelica). (Live from the Met, 14 November 1981, James Levine conducting the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra): Though she was a very different artist than Olivero, Renata Scotto was another of the greatest artists of her era, and, indeed, probably the greatest singing actress AC (After Callas). By the time she appeared in this live telecast, a 1981 reprisal of her 1975 feat of singing all three of the heroines in Puccini’s Trittico in one evening, her voice was beginning to unravel a bit, but one can still see exactly what made her so great. I would have loved to link to the closing pages of the opera, where she attains unbelievable expressive heights, but the quality of the sound and picture were simply too poor to be viewed with proper reverence. One has to ask just why this performance, and others from the recommencement of the Live from the Met telecasts in the 1970s and 80s is not available on a legitimate basis.

Arne Dørumsgaard (1921-2006). Peruvian Folk Song, arr. Arne Dørumsgaard: De aquel cerro verde [Robert Cornman, conductor, from the album Chants d’amour du monde, Le Chant du Monde, LD-A-8220/21, 1958]. The Norwegian musical and artistic polymath is an absolutely fascinating character. He was first promoted by the great Wagnerian soprano Kirsten Flagstad, who in the late forties began recording his original songs and arrangements of folk songs and arie antiche. Other artists followed suit, including several other of my favorite singers: Souzay, whose recordings of Dørumsgaard’s arrangements number among his most beautiful recordings (including Cachez, beaux yeux, Countermelody’s closing theme!), the Welsh tenor Richard Lewis, the Spanish mezzo Teresa Berganza, and the American mezzo Frederica von Stade. What is today perhaps less known is that Dørumsgaard himself possessed a modest but true baritone voice, which can be heard on a number of recordings from the late 50s and early 60s. I hope to connect with some Dørumsgaard experts and to be able to share more of his life and work with you in a future episode.

DIGGING DEEPER: MUZIO AND CECILIA:

I’m not sure that Muzio ever made a bad recording, but the ones listed here are others among my favorites. Of course there are other, probably even more famous ones (cf. the Addio del passato from Traviata ; La mamma morta from Andrea Chénier; Vissi d’arte [Tosca]; Pace, pace, mio Dio [Forza]; all from the late Columbia series); they’re all worth looking into, as well as her marvelous recordings of songs (the Muzio Song Recital record was given to me by my then-boyfriend for Xmas 1982 [thanks, Tim!])

Additionally, although I provided a brief biography of la Duse del canto in the podcast, I find that this article by Dean Southern on the Classical Singer Magazine website fleshes out the story with a few more details, and provides a breakdown of Muzio’s recordings with recommendations sometimes different than the ones I provide below.

I found a page that has an absolute wealth of relatively rare photos of Muzio, some of which simply must be seen to be believed. Check it out!

Umberto Giordano (1867-1948): Che me ne faccio nel vostro castello (Madame Sans-Gêne) (Pathé 82305, 1917). This, one of Muzio’s most accomplished Pathé recordings, is a forgotten gem from yet another Italian from the verismo era (it’s an open question if works like this are truly examples of verismo). This one, like Tosca, is based on a stage play by Victorien Sardou (1831-1908), and like Il Trittico, it received its world premiere at the Metropolitan Opera, starring Geraldine Farrar, Giovanni Martinelli and Pasquale Amato. A mere two years after its premiere, Muzio set down this beautiful aria in the recording studio, though she does not appear to have sung it onstage.

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924): Un bel dì (Madama Butterfly) ( Pathé 63018, 1917 ) Another of Muzio’s most successful Pathés, she also recorded Butterfly’s entrance for the label, though never again would she record music from this opera in the recording studio.

Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868): Selva opaca (Guglielmo Tell) ( Pathé 54025, 1918 ). Though she sings an abridged version of the aria, Muzio has a wonderful feel for the shape of the line. When I said I didn’t care for Rossini earlier, I wasn’t talking about this opera, or his serious operas in general, which are much more palatable to my taste.

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787): Spiagge amate (Paride ed Elena) ( Edison 82287, February 1923 ). Muzio here displays the particular qualities that are at the core of her artistry. She can spin a line like nobody’s business, and she knows how to get to the emotional core of a vocal line, displaying a delicious sense of rubato. One of her greatest Edisons.

Alfredo Catalani (1854-1893): Dove son (Loreley) (Edison 82300, March 1922 ). Muzio sang the title role in the Met premiere of this opera, making this recording immediately after the first performances. This role was also among her final roles at the Met until her apparently miraculous return twelve years later for one Santuzza and two Violettas, the only time she sang this role with the company. Here, as Loreley, she is incendiary. Along with the examples I played on the podcast, this is another of her finest recordings for the Edison label.

Stefano Donaudy (1879-1925): O del mio amato ben ( Columbia BQX 2504, June 1935 ). This is one of the heartbreakers in the Muzio discography. She had recorded the song earlier for Edison, but this version has no competitors. No one else comes close to capturing the devastation expressed in this song. The lover walks through a series of empty rooms where she once lived with the beloved. I don’t know if there’s any significance to this, but I love that Muzio does not change the female pronoun used to refer to the beloved.

Licinio Refice (1883-1954): Grazie, sorelle [Morte di Cecilia] (Cecilia) (Columbia BQX 1503, June 1935 [though some sources say April 1934]). Muzio reaches for and attains the heights here. Cecilia has been mortally wounded by her enemies and is brought back to a familiar scene where she has an ecstatic scene of the skies opening. When you hear Muzio solemnly intone the text: “Io salisco; ecco i giardini di luce, fontane di luce, abissi di luce,” [I am rising; behold the gardens of light, the fountains of light, the abysses of light], I hope that you, like I always am, will be carried into another world.

Francesco Cilea (1866-1950): Esser madre è un inferno (L’Arlesiana) (Columbia BQX 2507, June 1935 ). This aria, one which, as far as I know, Muzio sang exclusively for this recording, is actually written for the mezzo-soprano character of Rosa Mamai, the mother of Federico, the tenor. Cilea has the interesting distinction that Enrico Caruso premiered the tenor roles in two of his operas, this one in 1897 (like Zazà at the Teatro Lirico in Milano) and, five years later, Maurizio in Adriana Lecouvreur. Here Muzio once again demonstrates her ability to wring the full emotional content out of the text, in which she sings of the torture of being a mother, after she has narrowly prevented her son from killing his rival with a sledgehammer. (Interestingly, Opera Holland Park, revived Zazà in 2017.)

So much mention is made of the opera Cecilia, which was Muzio’s final stage creation, that I thought it would be helpful to include a link to a complete recording of the work, this one made for RAI on 29 October 1955 with conductor Oliviero de Fabritiis (1902-1982), leading Maria Pedrini (1910-1981), Alvino Misciano (1915-1997), and the Orchestra e Coro di Milano della RAI. I am not quite sure, because of my imperfect Italian, if the exceptional Pedrini was an actual protégée of Muzio’s or merely considered her spiritual successor in the role. At any rate, as you’ll hear, she is the real deal!

Renata Scotto (b. 1934). Licinio Refice: Per amor di Gesù and Grazie, sorelle (Cecilia). (Live performance, 13 December 1976, Angelo Campori conducting the Orchestra of the Sacred Music Society). Scotto’s gifts found their perfect outlet in this live New York performance of what I believe was the United States premiere of Refice’s curious hybrid. She is in fine fettle here, and while in Cecilia’s death scene, she chooses to emphasize the pathetic rather than the noble (as do both Muzio and Maria Pedrini [see above] in their recordings), she nonetheless makes a profoundly moving impression.

Maria Pedrini as Cecilia

Renata Scotto and Maria Callas

ABOUT ZAZÀ: THE PLAY

I fell down the rabbit hole of research into the original 1898 play by Pierre Berton (1842-1912) and Charles Simon (1850-1910). It appears that Berton was also celebrated as an actor, having created the roles in two plays by Victorien Sardou: Loris Ipanov in Fedora and Scarpia in La Tosca (interestingly in the operatic versions of these plays, one of these parts would be written for the tenor voice and the other for baritone). Charles Simon, on the other hand, was the son of the French statesman Jules Simon. To say that he has no internet presence other than as the co-author of Zazà would be an understatement.

The title role in Berton and Simon’s opus was originally played by Gabrielle Réjane (1856-1920), whose most famous stage creation was the title role in (guess!…) Sardou’s Madame Sans-Gêne, which she also filmed twice, the first time as part of a program of synchronized sound films at the 1900 Paris Exhibition (!) Though this YouTube clip is just a compilation of photos, it’s still fun to look at these and try to extrapolate from them what her acting might have been like.

The first actor to portray the title role in David Belasco’s (1853-1931) English-language version was the infamous Mrs. Leslie Carter (1857-1937), who went on to play Madame Du Barry in Belasco’s play of the same name. She eventually became known as “The American Sarah Bernhardt” and was celebrated as the most famous stage actress of her generation. In 1935, Carter appeared in a featured role opposite Randolph Scott (1898-1987) entitled either Rocky Mountain Mystery or, as it’s called in the version on YouTube, The Fighting Westerner. That same year she also played a supporting part opposite Miriam Hopkins (1902-1972) in Becky Sharp, the first feature film to use the three-strip Technicolor process. Five years later, Hopkins would herself impersonate Mrs. Carter star in a fictionalized biopic of her life called Lady with Red Hair; there is a short, amusing clip from that film available on YouTube. It is said that Mrs. Carter’s ghost still haunts the former Theater Republic, now called the New Victory Theater.

HOMO ALERT: Randolph Scott is also known as the man with whom Cary Grant kept house from 1932-1944

ARIAS AND SCENES FROM ZAZÀ

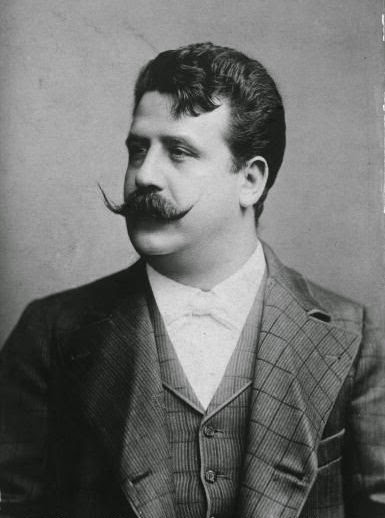

Ruggero Leoncavallo

(1857-1919) was the librettist for all of his operas except Edipo Re, his final one. It is disputed that the work was actually composed by Leoncavallo at all, but fashioned after his death out of material from one of his later operas, Der Roland von Berlin. Incidentally, Geraldine Farrar sang the role of Eva in the work’s 1904 Berlin premiere. Leoncavallo gave as much care and attention to writing of his libretti as he did to the composition of the music. (the text and English translation of Zazà is available here and the piano-vocal score of the 1919 edition of Zazà can be found at IMSLP).Emma Carelli

(1877-1928): Mamma usciva da casa (1906, Fonotipia XPh 1970); Dir che ci sono al mondo (1905, Pathé 4376). As mentioned in the podcast, Carelli had a wide-ranging repertoire and was particularly celebrated for her portrayal of Zazà. As with some of the other early verismo singers, Storchio included, I would guess that much of what made her so compelling onstage was not fully captured in the record grooves. Nevertheless, it’s interesting to listen to these excerpts.Geraldine Farrar

(1882-1867): Mamma usciva da casa + Non so capir “Il bacio” [with Giuseppe de Luca]) (1920, RCA Victrola 87568). Zazà has not been revived at the Metropolitan Opera since Geraldine Farrar took her leave of the operatic stage at the age of only 40 following her 23rd performance of the role, which she stated was her favorite part. De Luca played the role of Cascart opposite her for the majority of performances. Their charming interplay is heard in their 1920 recording of the scene of their diegetic number from the first act sometimes called “Il bacio.”Clara Petrella

(1914-1987): Mamma usciva da casa… Dir che ci sono al mondo (1969, RAI). In the podcast I devote a certain amount of attention to the strange performing edition of Zazà that was evidently commissioned by Sonzogno, Leoncavallo’s publisher, nearly 30 years after his death. As I mentioned, this is the version that is often performed and recorded (including, among others, this version, as well as studio recordings of the aria by Montserrat Caballé and Diana Soviero). Petrella gives a lovely performance here in many ways, but the rewriting of the vocal line removes much of the poignancy from the music. Compare Petrella’s excellent version to Muzio’s and you will see what is missing. Again, this is not to criticize Petrella, but simply to emphasize the wrong-headedness of this truncation and revision of the score in which Leoncavallo himself played no part. I have not remarked on this elsewhere in the Show Notes or on the actual podcast, but it is worth noting that the role of Totò is a speaking one, which when performed by a good actress, as is the case here, extracts the maximum pathos out of the scene. (Dir che ci sono al mondo begins at 3’44”)Eva von der Osten

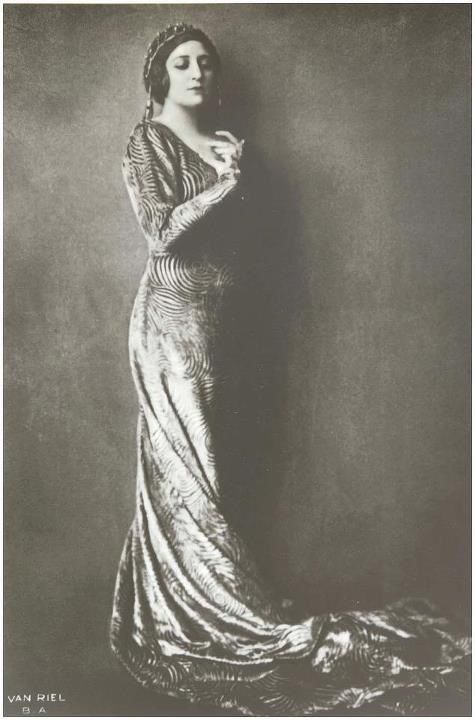

(1881-1936): Geh, schilt mir nicht die Mutter [Via, non mi torturate] (1908, Gramophone 2-43197); Was wird, Mylio, aus mir [Amor mio, che farà non più vicina] (1908, Gramophone 2-43198). As I mentioned on the podcast episode, von der Osten is most famous for having created the role of Octavian in 1911, several years after the Zazà excerpts presented here were recorded. Today it would be considered quite extraordinary to encounter a singer who had such a wide range of repertoire as did von der Osten, who was particularly celebrated for her Isolde, and in fact, virtually all the Wagner heroines (and villainesses). Her acting was found to be of the most affecting quality, and this quality can certainly be heard in the two Zazà excerpts heard here sung in German.Mafalda Favero

(1905-1981), Giacinto Prandelli (1914-2010): Act IV Finale. [Live audio recording conducted by Franco Ghione from Teatro di San Carlo di Napoli, 1950]. Mafalda Favero is a fascinating artist. As beautiful as a movie star (she in fact appeared in the 1940 film Musica di sogno), she possessed a piquant voice which was featured in the premieres of operas by Franco Alfano, Pietro Mascagni, Riccardo Zandonai, and Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari. If you listen to this excerpt, you will note that she pushed that voice to its absolute limit. That goes double for her live 1947 Butterfly from Geneva, which appeared by some miracle on YouTube a few years ago and nearly caused me to lose my mind. She does absolutely everything that a singer is taught that she should not do, and yet she creates a hair-raising impression. Yet she is quoted as having said “the role of Cio-Cio San was my ruination… to sing it as I did, giving everything and then some, exacted an enormous price… I am quite aware the Butterfly cut short my career by at least five years.” She exhibits the same over-generosity here, but OMG, it’s amazing. One must also mention Prandelli here, who was a superb tenor who had an international career in the 50s and 60s, excelling not only in the Italian repertoire, but in Mozart and French roles as well. Among other achievements, he sang at the La Scala premiere and in the first recording of Giancarlo Menotti’s Amelia al ballo.Denia Mazzola Gavazzeni

(b. 1953), Luca Canonici, Stefano Antonucci, and others: End of Act I; beginning of Act II, [Live performance conducted by Gianandrea Gavazzeni, Teatro Massimo, Palermo, January 1995]. This excerpt is refreshing because it is of one of Leoncavallo’s genuine versions and features several highlights. It must also be mentioned that Denia Mazzola Gavazzeni, here conducted by her husband, the distinguished Gianandrea Gavazzeni, is exceptionally good in the title role, capturing the essence of the character and singing with the exact balance of technique and abandon that in my opinion makes for the perfect approach to this repertoire. After beginning her career as a more than respectable lyric coloratura soprano, she gradually moved into heavier roles, having a particular success as Massenet’s Esclarmonde. She has been involved in live performances and recordings of some of the most fascinating revivals of obscure repertoire, including Mirra (1920) by Domenico Alaleona (1891-1928), Cassandra (1903) by Vittorio Gnecchi (1876-1954), Marion Delorme (1885) by Amilcare Ponchielli (1833-1886), Risurrezione (1904) by Franco Alfano (1875-1954), Parisina (1913) by Pietro Mascagni (1863-1945) L’amore di tre re (1913) by Italo Montemezzi (1875-1952), and, once again… Licinio Refice’s Cecilia (1933).Patricia Craig

(b. 1947), with Charles Long: Act II Finale [Live performance conducted by Anton Coppola, Cincinnati Opera, 1985]. For its 1985 season, Cincinnati Opera produced a rare and well-cast revival of Zazà, an excerpt of which is now available on YouTube. It featured the marvelous lirico-drammatico soprano, Patricia Craig, who had a long and distinguished career, performing frequently at the Met, though never in this opera, which has not been seen there since 1922. She was married to Richard Cassilly, the distinguished American heldentenor, until his death in 1998. Here, joined by the excellent baritone Charles Long, she infuses the role of Zazà with pathos and vocal glamour, proving her mettle as a specialist in this repertoire.Aprile Millo

(b. 1958), with Gerard Powers: End of Act Four conducted by Alfredo Silipigni. [Live perofrmance, Teatro Grattacielo, New York, 12 November 2005]. The American lirico-spinto soprano had a long run at the Metropolitan Opera from the mid-1980s through the late-1990s with occasional performances since then. She has always interested herself in the verismo repertoire in addition the Verdi roles which she sang most frequently at the Met. In 2005 she was presented by the intrepid company Teatro Grattacielo in a single concert performance of Zazà. On the basis of this excerpt, it seems as if Alfredo Silipigni (who conducts the 1969 RAI performance as well as a New Jersey State Opera run in 1986 with the Italian soprano Silvia Mosca) once again chose to perform the questionable Renzo Bianchi version, which changes the ending of the opera significantly from Leoncavallo’s original. More’s the pity, because it sounds like this was a very good performance in most other ways.There are also a number of historically important recordings of tenors and baritones who featured in early performances of the opera.

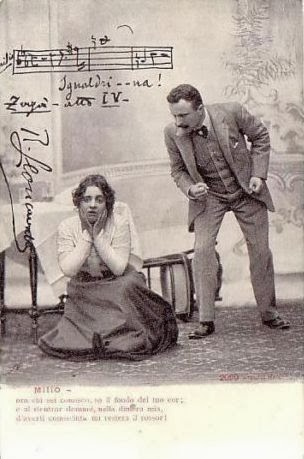

Edoardo Garbin (1865-1943): Mai più, Zazà (Fonotipia 92253, 1908) Although the name of the Italian tenor Edoardo Garbin is not terribly well-known today, he in fact created the roles of Fenton in Verdi’s Falstaff (1893) and Milio in Zazà, as well as Don Guevara in Alberto Franchetti’s (1860-1942) Cristoforo Colombo (1892). In this excerpt, the second part of the longer aria O mio piccolo tavolo, he reveals a firmly focused, nasal timbre that is supported by a solid technique. John Steane in The Grand Tradition describes his voice as “a curious mix of the frail and explosive,” which sounds about right.

Giulio Crimi (1885-1939): O mio piccolo tavolo (Vocalion 55006, recorded 1922(?)). Giulio Crimi, like Garbin, is not a recognized artist these days, but he sang over one hundred performances at the Met over four seasons (1918-1922), creating the role of Luigi in the world premiere of Puccini’s Il Tabarro, which he sang opposite the Giorgetta of Claudia Muzio. It is a pity that no recordings of this were preserved. He also sang Milio in the first Met performances of Zazà, sharing the role with Giovanni Martinelli. Each is featured here in one of the character’s two arias. This one is heard at the beginning of the third act where Milio is preparing to bid Zazà farewell for the final time, in spite of his memories of their passionate lovemaking. Crimi gives a powerful reading.

Giovanni Martinelli (1885-1969): È un riso gentil (RCA Victor 66062, November 1927). The dramatic tenor, possessor of what seems like a more sizeable instrument than Crimi’s, shared the role of Milio with him during the four seasons when Farrar championed the title role. Here the foremost Otello of his generation faces up against this charming canzonetta, in which he describes Zazà to her friend Bussy as a dangerous conquest. While I am not the world’s biggest Martinelli fan (I find his tone a little hard and nasal and his delivery sometimes inelegant), but considering the size of his voice, he dispatches the rapid fire writing of this aria with relative charm and aplomb.

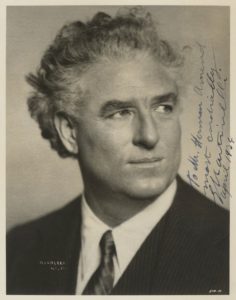

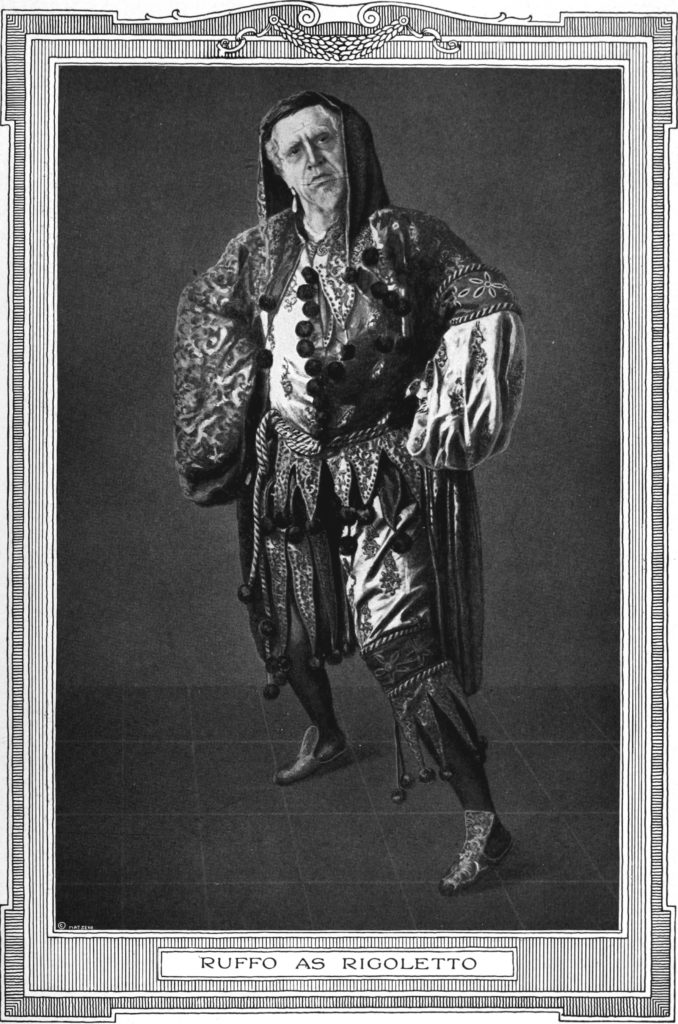

Titta Ruffo (1877-1953): Buona Zazà del mio buon tempo (RCA Victor 87114, November 1912). The role of Cascart is a marvelous one. The baritone Charles Long, who sang it opposite Patricia Craig in the 1985 Cincinnati performances, described it as “Tonio and Silvio [the two contrasting baritone roles in Pagliacci] rolled into one.” Cascart is Zazà’s stage partner and former lover. In their interactions it is clear that he still carries a torch for her. In this aria, he tells her that her lover Milio has been seen in Paris with another woman. Though he frames his disclosure as stemming from loving concern, it is more than possible that he is hoping to end the union of these two so as to reunite with Zazà himself. The extraordinary Titta Ruffo, renowned as the “voce del leone” [“voice of the lion”] was famous for his interpretation of the role of Cascart, though he did not sing it at the Met. Such distinguished colleagues as Victor Maurel and Giuseppe de Luca declared Ruffo’s voice to be a flat-out miracle. He certainly possessed one of the finest baritone voices ever captured by the recording horn.

Giuseppe Danise

(1882-1963): Buona Zazà del mio buon tempo (Brunswick J 2048, November 1922). Giuseppe Danise was a fine singer and became renowned after his retirement as a significant vocal pedagogue, numbering among his students Regina Resnik, Giuseppe Valdengo, Barry Morell, and Bonaldo Giaiotti. After a distinguished career in Italy and South America (which included recording the role of Rigoletto for La Voce del Padrone in 1916, the first complete recording of the opera), he emigrated to the United States, where he sang more than 400 at the Metropolitan between 1920 and 1932, often paired with the greatest singers of the age, including many I have already mentioned but also including Emmy Destinn, Amelita Galli-Curci, and Beniamino Gigli. He also sang in the Met premiere of Catalani’s Loreley opposite Muzio. He and the Brazilian soprano Bidú Sayão (see SECTION 2: ARTISTS MENTIONED IN THE EPISODE) were companions for many years, and in 1946 they finally divorced their respective spouses and got married. In the same scene that Ruffo also recorded, Danise reveals a voice of extraordinarily good quality, finesse, and expressiveness.Mario Sammarco (1868-1930): Zazà, piccola zingara (Gramophone 52373, March 1902). If you have not heard of Mario Sammarco, you are about to: not only did he create the role of Cascart, but, even more significantly, he was the first Carlo Gérard in Giordano’s Andrea Chénier (1896). It must be said that he is included here more for his historical significance than for the excellence of his recordings. In general they are considered to be disappointing. He was not a bel cantist: he was much more comfortable bellowing away in the blood and guts of the verismo repertoire. He has a notorious recording of a portion of Puccini’s Tosca opposite Emma Carelli in which he punctuates his lines and interrupts hers with endless guffawing. By comparison, he is relatively well-behaved in this, the most famous excerpt from Zazà and a former baritone favorite on recitals and concerts.

Pasquale Amato (1878-1942): Zazà, piccola zingara. (Fonotipia X 62175, March 1907). During his tenure at the Metropolitan, which numbered more than 600 performances, Pasquale Amato had few rivals and no superiors. He created roles in the Met premieres of many works, including Madame Sans-Gêne, Riccardo Zandonai’s Francesca da Rimini, Pietro Mascagni’s Lodoletta, Alberto Franchetti’s Germania, Jules Massenet’s Thaïs, Italo Montemezzi’s L’Amore di tre re, and Leoncavallo’s Zazà, among many others. One of his rare German roles was Kurwenal in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. He was also Jack Rance in the 1910 world premiere of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West opposite Emmy Destinn and Enrico Caruso. His voice might not have been as powerful as Ruffo’s, but it had a beautiful evenness and sheen to it. In this aria from Zazà’s final act, Cascart attempts to comfort his former beloved in her heartbreak. This recording was made in Italy before Amato crossed the Atlantic to come to the Met.

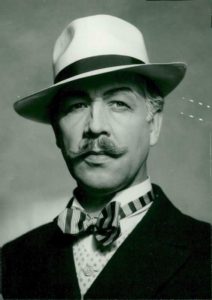

Giuseppe de Luca (1876-1950): Zazà, piccola zingara (Fonotipia xPh 227, 1905). Giuseppe de Luca, who shared the role of Cascart with Amato during the Met tenor of Zazà, also created a significant number of world premieres, including Madama Butterfly at La Scala alongside the aforementioned Rosina Storchio, and Gianni Schicchi in the 1918 Met world premiere of Il Trittico. Other operas in which he participated in the world premieres include Massenet’s Don Quichotte opposite Feodor Chaliapin, Giordano’s Siberia (again opposite Rosina Storchio), and Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur, among others. He sang even more performances at the Met than did Amato (more than 900, according to the Met Archives). Toscanini himself stated that de Luca’s was “absolutely the best baritone” he had ever heard. De Luca is here pictured with Muzio in the 1920 United States premiere at the Met of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, which was originally performed in Italian. De Luca’s recording of Zazà, piccola zingara, like Amato’s, was recorded before he ever sang at the Met.

FILM ADAPTATIONS OF ZAZÀ

Smouldering Fires (1925). Though Pauline Frederick’s 1915 silent version of Zazà, her third film, is now considered lost, as is the vast majority of her extensive filmography, one can still see her in a later film, Clarence Brown’s 1925 opus, Smouldering Fires. Though she is virtually unremembered today, Pauline Frederick made a slew of silent films and even made a successful transition to talkies, playing Joan Crawford’s mother in This Modern Age (1931). The illustrator Harrison Fisher, one of her early supporters, called her “the purest American beauty.” She was, indeed, as you can see, stunningly beautiful. After several years of declining health, she died of a severe asthma attack in 1938 at the age of 55. Interestingly, she starred in three 1918 films that also exist in verismo operatic versions: La Tosca (Puccini, 1899); Resurrection (Alfano, 1904); and Fedora (Giordano, 1898).

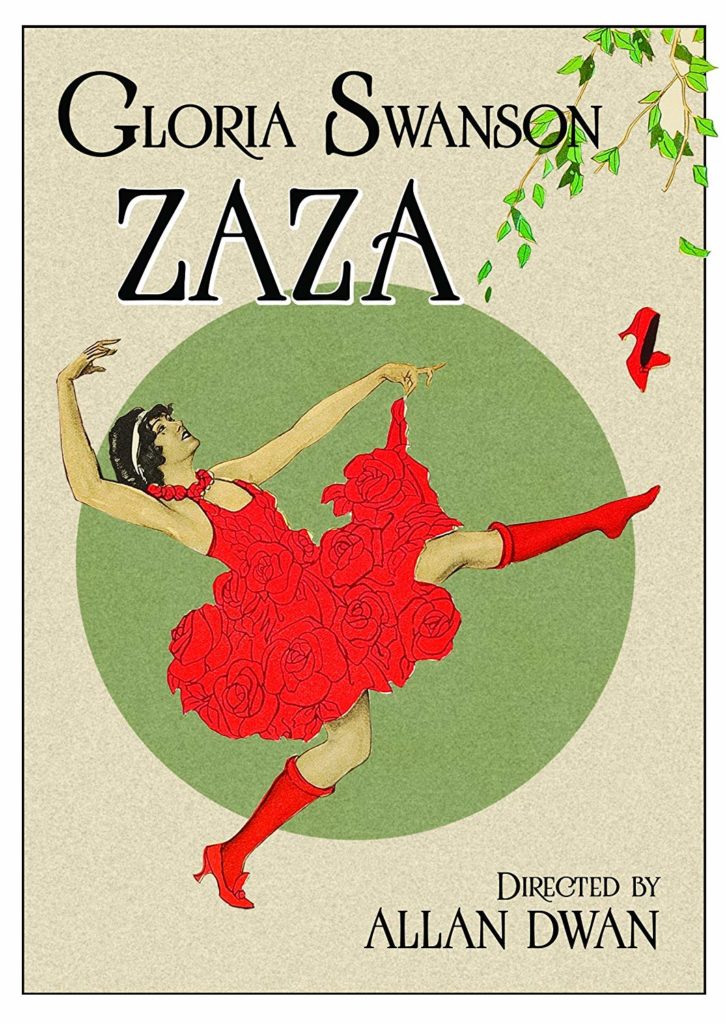

Zaza (1923). Anything with Gloria Swanson is sehenswert, as we say here in Deutschland, and this 1923 silent, directed by Allan Dwan, known primarily for his longevity and for being a prolific workhorse (407 directing credits between 1911 and 1961!), is no exception. Here she plays the role of Zaza in incandescent overdrive mode. The role of her lover, here named Bernard Dufresne, is played by H.B. Warner, remembered today for his onscreen turn as Jesus in Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings. He’s also featured in It’s a Wonderful Life, (a film which, if I were never to see it again, it would be too soon), and is reunited with Gloria Swanson for a cameo in Sunset Boulevard. Two interesting operatic sidelights about the leads of Zaza: First, Swanson played the title role in the 1925 French-American film production of Madame Sans-Gêne, which, though a critical and box office success, is now lost. Second, Warner plays the secondary role of Father Sienna in the 1938 non-operatic version of The Girl of the Golden West, starring Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, which evidently features a passel of songs by Sigmund Romberg and Gus Kahn (IDK; I’ve never seen it).

In addition to the versions I’ve already mentioned, there are several other films based on Zazà (unavailable on any platform of which I am aware) including:

- a Hollywood production starring Claudette Colbert (George Cukor, 1938) (this features a song by none other than Friedrich Hollaender);

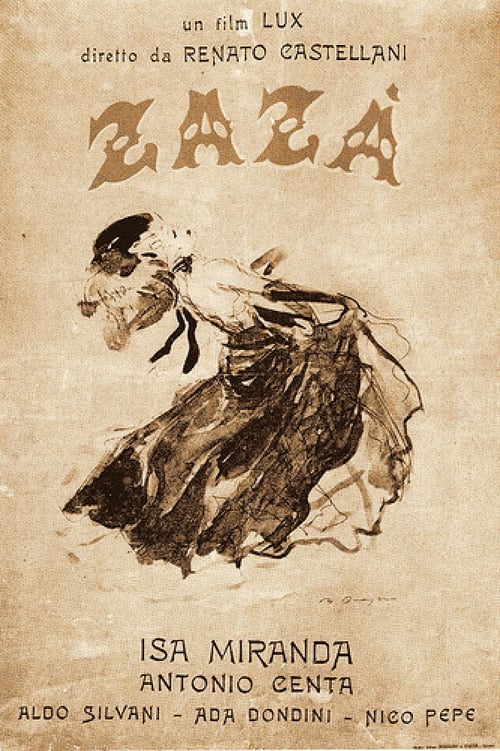

- an Italian production starring Isa Miranda (Renato Castellani, 1944) (Isa Miranda was the original star of the 1938 film but had to withdraw; she nevertheless starred in the subsequent remake in her native Italian;

- and a French production starring Lilo (René Gaveau, 1956).