Episode 2: A Countertenor for the 21st Century: Interview with Nicholas Tamagna (Part One)

SOCIAL SHARE:

SUBSCRIPTION PLATFORM

I am excited to offer as my guest for the next two episodes the marvelous young American countertenor Nicholas Tamagna. Nicholas sat down with me this past June to discuss many different aspects of countertenordom, including in-depth discussions of several recent productions of Handel and Monteverdi operas in which he was involved and the challenges of performing these different musical styles and dramatic contexts. We also discuss the route by which Nicholas discovered his countertenor voice, the joys of playing comedy and flawed heroes, and his childhood fascination with language, and how that has served him in good stead in his performing career. The episode, which also features numerous recent live clips of Nicholas singing, concludes with our discovery of our mutual love for an iconic French film. Please join us next week for the conclusion of this interview.

NICHOLAS TAMAGNA BIO

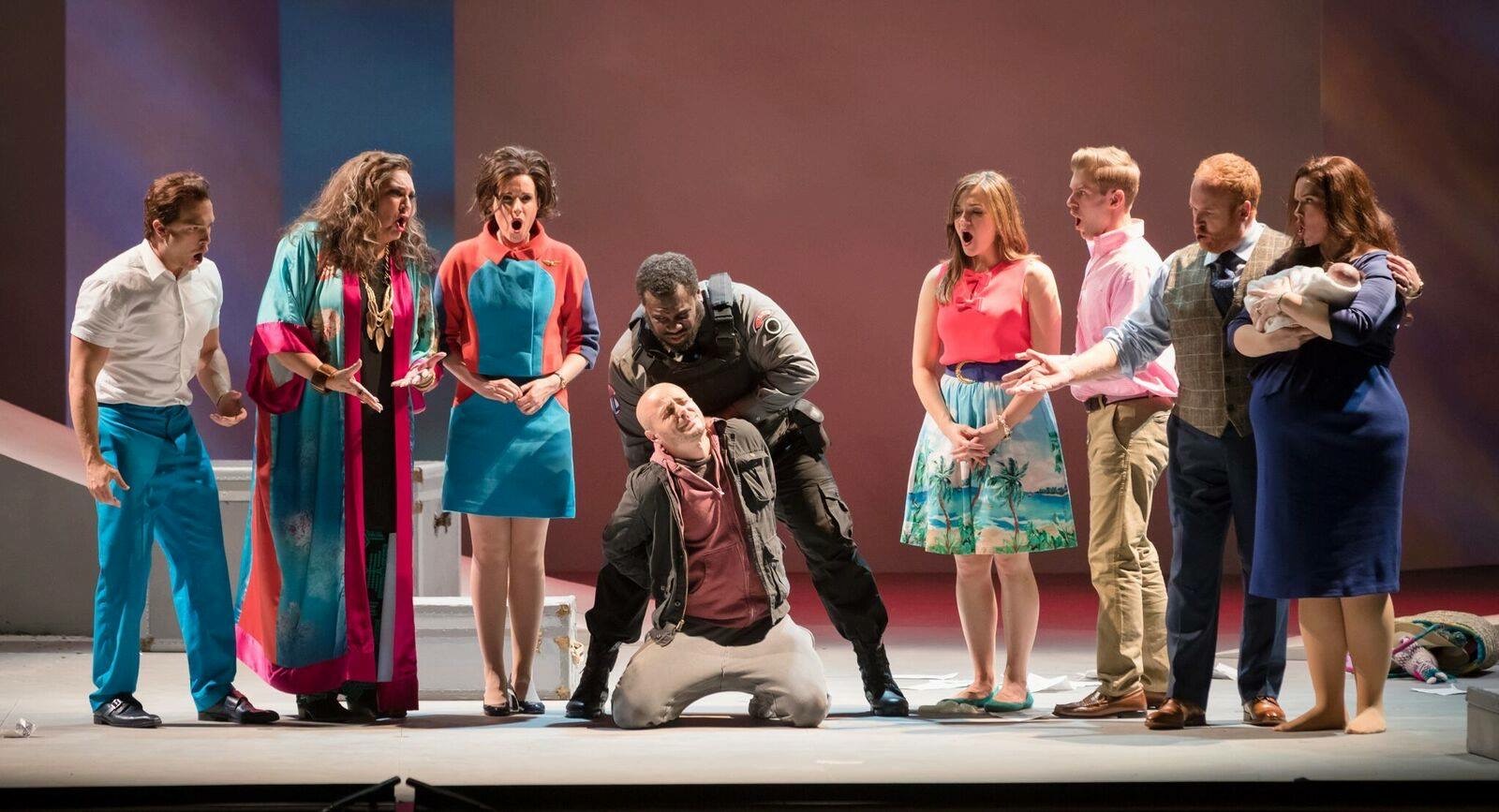

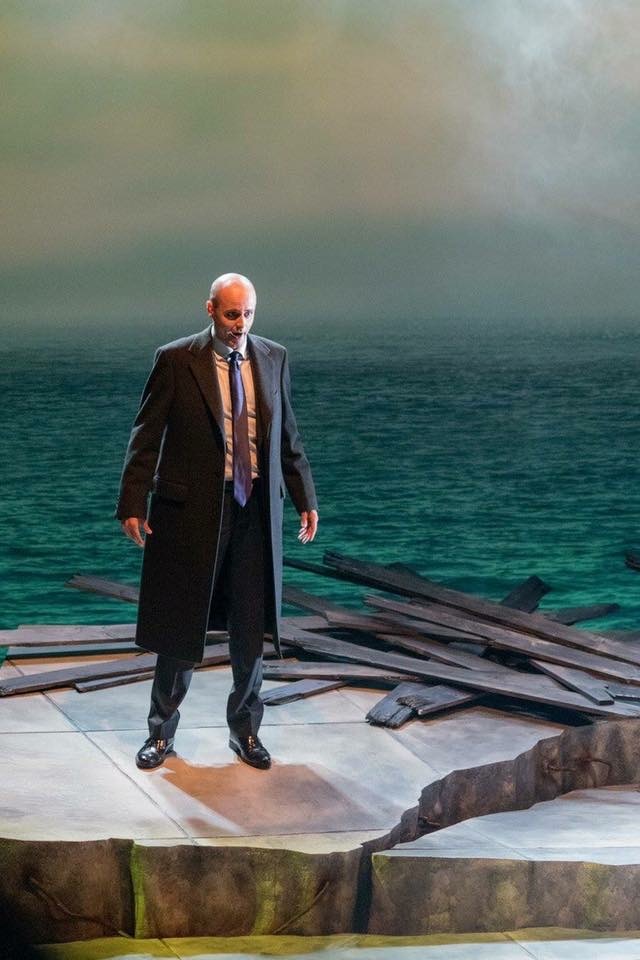

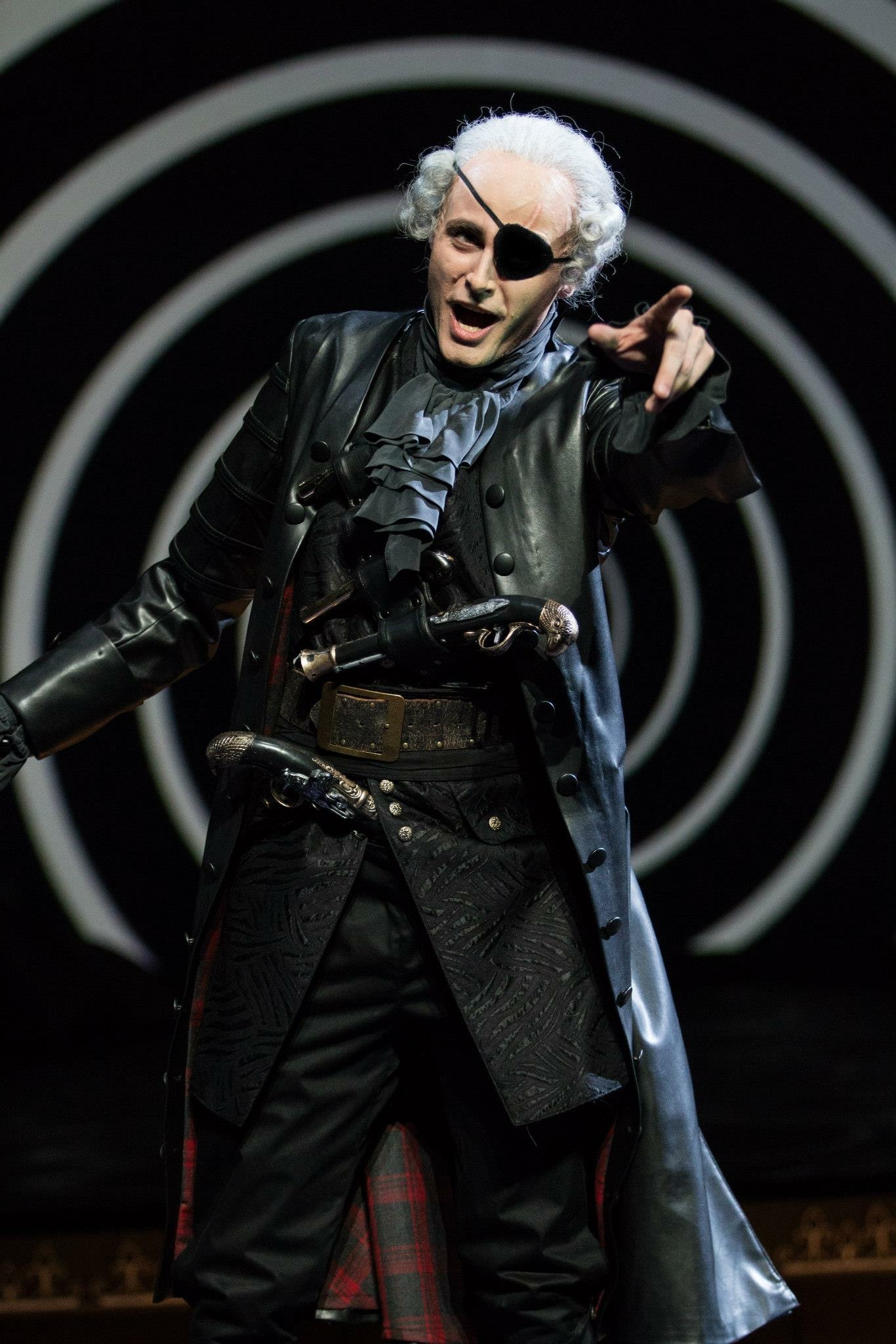

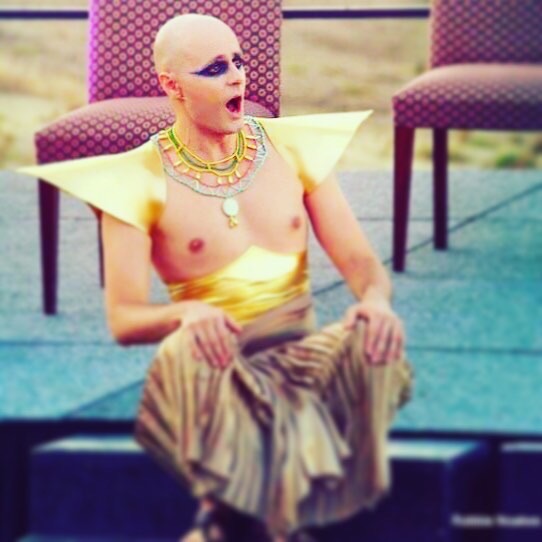

Countertenor Nicholas Tamagna has garnered widespread acclaim for his commanding expressive vocal timbre, his breathtaking musicianship, and superb acting skills; establishing himself as a leading countertenor in his generation. The New York Times has described him as a “standout… singing with a luminous countertenor, strong coloratura and dramatic conviction.” In 2019 he joins the Wiener Staatsoper and Metropolitan Opera making his debuts in both houses covering productions of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream as Oberon and Handel’s Agrippina as Narciso, respectively. In the past season, he was twice featured at the Händelfestspiele Halle appearing as Silvio in Handel’s ll Pastor Fido and as Ruggiero in Handel’s Alcina. Earlier this year, he was also heard as Ottone in L’incoronazione di Poppea with the Florentine Opera Company in Milwaukee, WI. In the fall of 2019 he will tour Germany and Switzerland with Lautten Compagney in his premiere assumption of the title role of Handel’s Rinaldo in addition to reprising the role of Ruggiero in Alcina. In 2018 he made his debut at Theater an der Wien and Victoria Teatru in Gliwice, Poland with Parnassus Arts Productions in a special concert presentation of Gismondo, Re di Polonia by Leonardo Vinci, a role he just recorded last month for December 2019 release, and which tours this season in Poland. He will also return to the Nederlandse Reisopera for their production of Handel’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto as Tolomeo in 2022, a co-production with the Göttingen Händelfestspiele. Further upcoming performances include Bertarido in Handel’s Rodelinda at the 2020 London Festival of Baroque Music, and at the Oldenburgisches Staatstheater; and the role of Turio in Hasse’s Cajo Fabrizio with Parnassus Arts. Also active in the field of contemporary opera, he will return to the Oldenburgisches Staatstheater in 2020 for their production of Jonathan Dove‘s Flight in the central role of The Refugee, a role he first sang with Opera Omaha in 2017. He has also twice sung Philip Glass’s Akhnaten, in Indianapolis and Melbourne.

Nicholas Tamagna’s international career first began in 2014 with the role of Oronte in Handel’s Riccardo Primo with the Badisches Staatstheater Händelfestspiele in Karlsruhe directed by Benjamin Lazar. Since then he has also sung the title role and toured in a much-acclaimed co-production of Hasse’s Siroe, Re di Persia with the Nederlandse Reisopera in eight cities in the Netherlands and at the Oldenburgisches Staatstheater in Germany. He also made his debut with the Musikfestpiele Potsdam at the Sanssouci Palace as Amore in a production of L’Europa by Alessandro Melani directed by Deda Christina Colonna. He has also sung at the Spoleto Festival USA and the Opéra de Haute-Normandie Rouen as well as at Carnegie Hall. His recording entitled “Son of England: Music of Jeremiah Clarke and Henry Purcell” with Vincent Dumestre and Le Poème Harmonique is currently available on the Alpha Classics label.

Nicholas appears on two new recordings this fall. One, entitled Ring Out, is a collection of compositions by Jessica Meyer. Nicholas performs in Seasons of Basho, a four-song cycle to texts by the Japanese poet Matsuo Basho scored for countertenor, viola, the composer herself, and piano, played in the recording by Adam Marks. The album is available on the Bright Shiny Things label. The second CD is of songs by the self-taught and heretofore virtually unknown composer, Lola Williams (1913-2013), whose music contains echoes of Delius and Mahler. On this recording Nicholas performs alongside soprano Sarah Mouton Faux and pianist Ted Taylor. Where Should This Music Be? is now available on the New World Records label.

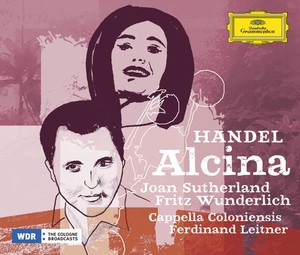

RECORDINGS FEATURED ON THIS EPISODE

Handel: Musette from the Overture to Alcina. During my reading of Nicholas’s biography, I played an excerpt from the Overture to Alcina, one of the operas in which Nicholas recently appeared with the Händelfestspiele Halle. Because I am so “old school” I chose to use the recording of an historic radio broadcast featuring Ferdinand Leitner and the Cappella Coloniensis. The 1959 Westdeutscher Rundfunk recording marks the only time that Joan Sutherland and Fritz Wunderlich appeared together. Others featured in the case include the recently departed but unforgettable Norma Procter, Nicola Monti, Jeannette van Dijck, and Thomas Hemsley. In 2008, it received an official release on Deutsche Grammophon.

Handel: “Non vuò legarmi il cor“ from Il pastor fido. Here is Nicholas in a live video excerpt from his performance at this season’s Händel-Festspiele Halle. A Parnassus Arts Productions event with {oh!} (the orkiestra historyczna ).

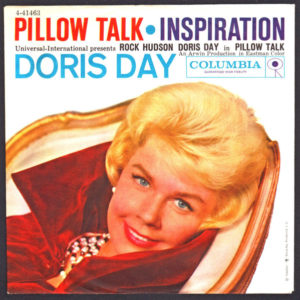

Doris Day: Pillow Talk (Columbia Records 4-41463, Orchestra directed by Jack Marshall). The beloved singer and actress died in May at the age of 97. The song quoted in the episode where Nicholas describes a staged pillow fight, is the theme song of the 1959 film starring Doris Day and Rock Hudson, the first of their three films together. It features a jaw-dropping scene in which Hudson, closeted in real life, “pretends” to be gay. Amazingly the screenplay won an Oscar in 1960, beating out both Truffaut’s The 400 Blows [Les Quatre Cents Coups] and Bergman’s Wild Strawberries [Smultronstället]. A contemporary review skirts over the more troublesome aspects of the script, while more recent assessments by Matthew Kennedy and, particularly, Pamela Robertson Wojcik, address them head-on.

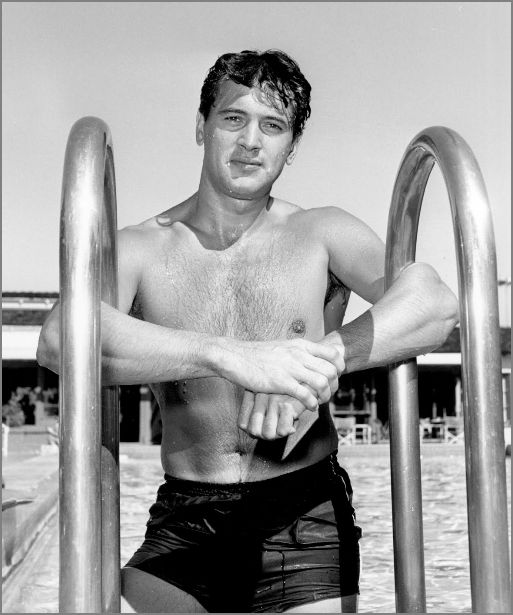

HOMO ALERT #1: Rock Hudson! For those interested in exploring more about the legendary Hollywood icon, the new biography by Mark Griffin, All that Heaven Allows, looks like the perfect starting point. Others might prefer to simply moon over beefcake photos.

The Elmer Fudd quote is from from the Warner Brothers Merrie Melodies cartoon Rabbit Fire (1951).

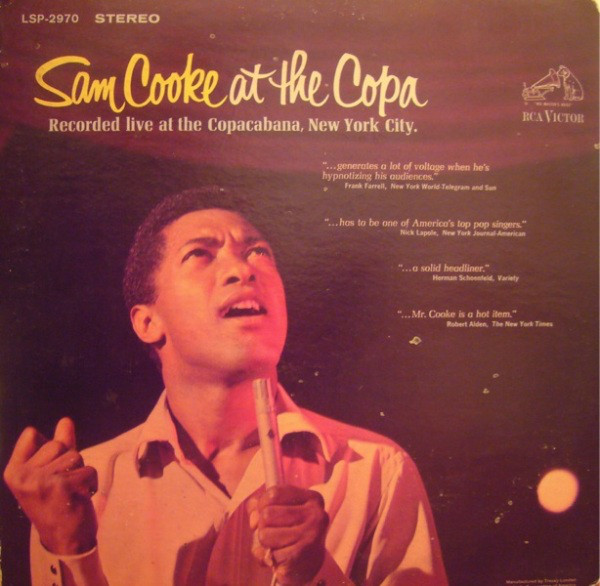

Sam Cooke: This Little Light of Mine. (from Sam Cooke at the Copa, RCA Victor LSP-2970). He’s been called the greatest, most important soul singer of all time. You get no argument from me. Just listen to him in this live clip recorded shortly before his untimely death at the age of 33. It’s all there: the sheer voice, the playfulness, the reverence, the musicianship, the fervor.

Nicholas Tamagna: “Verdi prati” from Handel’s Alcina. Live performance from the Goethe Theater, Bad Lauchstädt, as part of the Händel-Festspiele in Halle featuring Lautten Compagney.

Monteverdi: “I miei subiti sdegni” from L’incoronazione di Poppea. Daniel Gundlach, countertenor; Daniel Beckwith, piano. This is from a demo I made quite a few years ago. Except for the short excerpt heard in this episode, it is not currently available online.

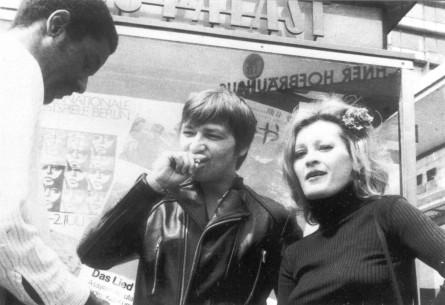

Les parapluies de Cherbourg . I included a clip from the soundtrack of the iconic 1963 film directed by Jacques Demy that helped cement the reputation and formulate the legend of actress Catherine Deneuve, who is positively incandescent in the role of Geneviève Emery. She is by no means the only element in the film’s success. The score by Michel Legrand, who died earlier this year, features the unforgettable theme song, “Je ne pourrai jamais vivre sans toi” or “I Will Wait for You.” In fact, the film is extraordinary in that every line of dialogue is sung (albeit dubbed). One must also mention that Deneuve’s costar Nino Castelnuovo, though nowhere near as celebrated as Mme. Deneuve, has been featured in films from Luchino Visconti’s (HOMO ALERT #2!) 1960 masterpiece Rocco e I suoi fratelli [Rocco and His Brothers] to 1996’s The English Patient. In addition to its stunning score, Les parapluies is celebrated for its astonishing use of color. This article by Jim Ridley, which accompanied the restored film’s presentation as part of the distinguished Criterion Collection, highlights many of the reasons for the film’s enduring popularity.

LINKS TO SUBJECTS, WORKS, AND PERSONS DISCUSSED IN EPISODE 2:

Baroque gesture: A website and an article that discuss the basics of Baroque gesture.

Modern acting style: I find the oversimplistic explanations on the Wikihow website to be some of the most hilarious bits of data available on the interwebs. This page on Method Acting is no exception. It’s not quite as good as their pages on How To Sing, but it’s still good for a laugh.

Some fascinating recordings of L’incoronazione di Poppea:

Here is a link to the 1993 Schwetzinger Festspiele production of the opera, one of the better-sung period-instrument versions available on YouTube (Jeffrey Gall as Ottone is particularly good).

I’m also rather fond of the 1979 Jean-Pierre Ponnelle-directed, Nikolaus Harnoncourt-conducted version from Zürich featuring Éric Tappy (who will be featured on my upcoming “Swiss Misses [and Misters]” episode) as Nerone, the marvelous Rachel Yakar (a protégée of the great Germaine Lubin!) as Poppea, and Trudeliese Schmidt (sister of Ingrid Caven, the former wife of Rainer Werner Fassbinder: [HOMO ALERT #3!]) as Ottavia.

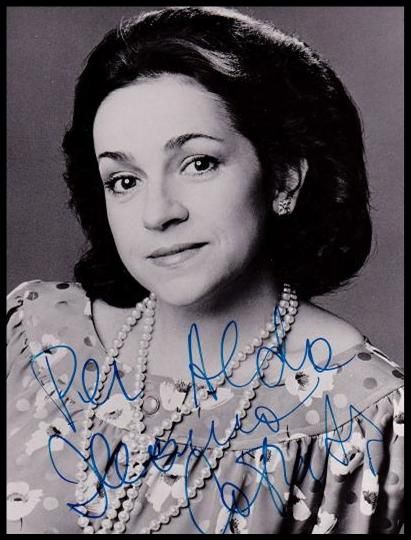

If you prefer a version featuring the exquisite Jurinac as Poppea and my beloved as Drusilla, and don’t mind wading through some pretty heavy-handed and heavily-accented singing from a few of the others as well as some elephantine tempi, check out this version conducted by Herbert von Karajan at the Wiener Staatsoper in 1963. Just be warned: it don’t sound much like Monteverdi!

Another deliciously unstylistic version is the recording of the edition prepared for Glyndebourne by Raymond Leppard and featuring, among others, the superlative Welsh tenor Richard Lewis as Nerone the intrepid and versatile Hungarian soprano Magda László as Poppea the under-recorded American mezzo-soprano Frances Bible, and the extraordinary Mexican mezzo Oralia Dominguez as Arnalta.

And while we are on the subject of the rather fulsome Raymond Leppard realizations of early Baroque operas, I beg you to take a look at the legendary 1971 Glyndebourne production of Cavalli’s La Calisto starring two of my all-time favorite singers, Ileana Cotrubas and Janet Baker.

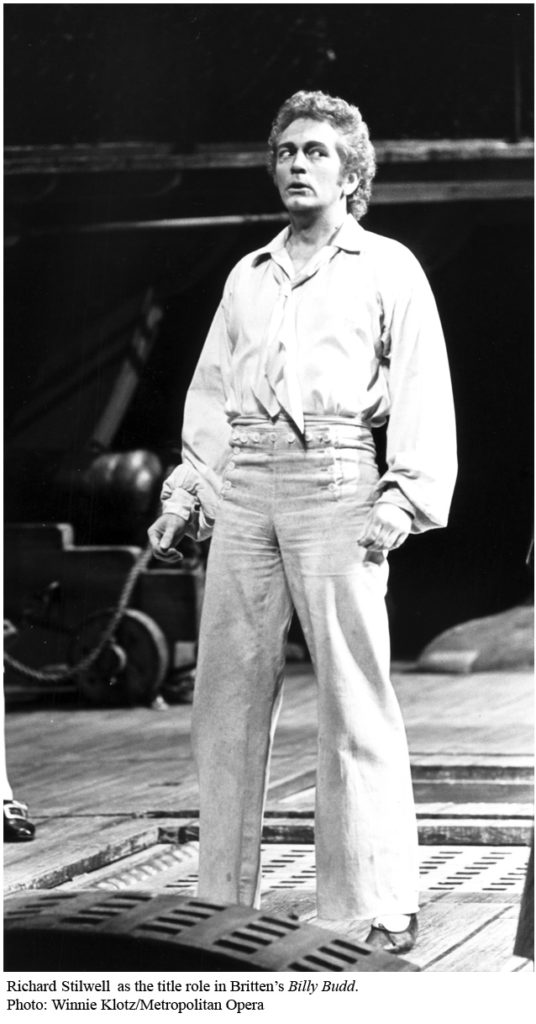

Finally, for a live Poppea that pulls out all the stops to the extent that it might be mistaken for Wagner, don’t neglect to check out this live 1978 version from the Paris Opéra with Julius Rudel conducting Gwyneth Jones (Poppea), Jon Vickers (Nerone) [HOMOPHOBE ALERT!], Christa Ludwig (Ottavia), Richard Stilwell (Ottone), and Nicolai Ghiaurov (Seneca), among others. It might not sound much like the Monteverdi one would hear today, but it’s pretty amazing on its own terms!

In addition, this article by Wendy Heller offers some fascinating insights into the political climate of Monterverdi’s Venice as well as the historical situation in Rome at the time of Nerone, Poppea, Ottavia, Seneca, and Ottone.

Robin Guarino directed the Incoronazione di Poppea that Nicholas sang at Florentine Opera in April 2019.

St. Boniface Church, Brooklyn, NY. The church job at which Nicholas almost by accident began to learn how to realign his countertenor voice.

Nicholas mentioned four countertenors in the course of the interview. I offer relevant links to those wishing to discover more about these singers: David Daniels; Brian Asawa; Alfred Deller; Russell Oberlin.

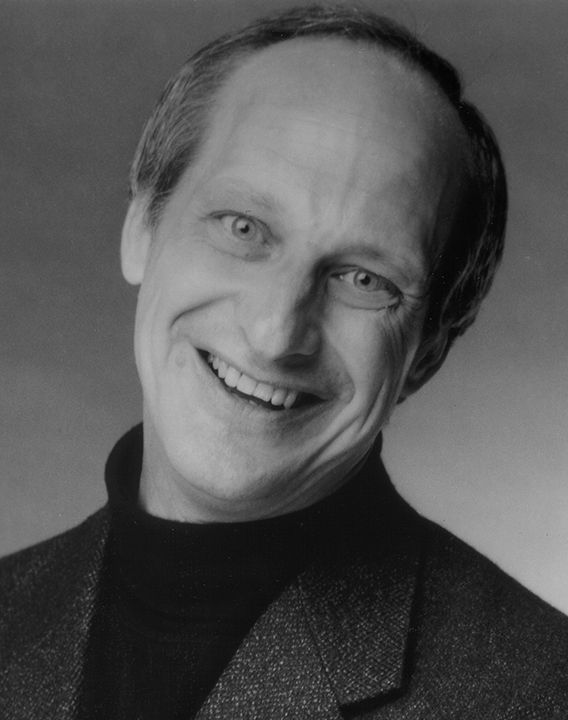

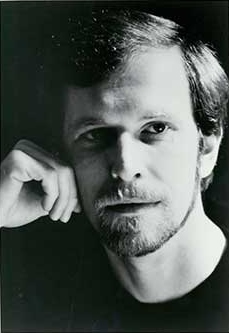

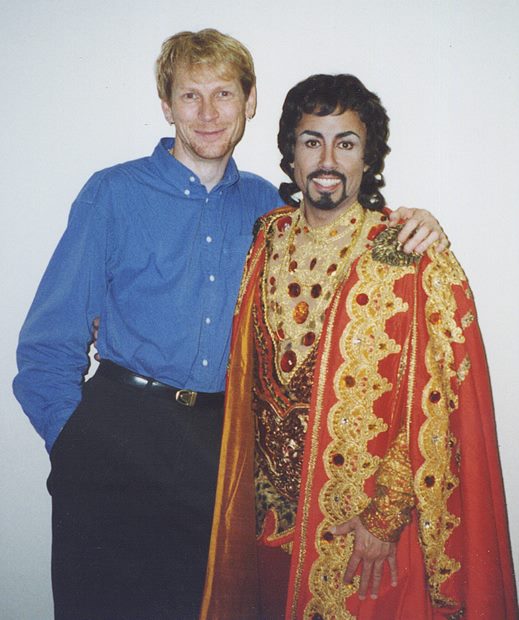

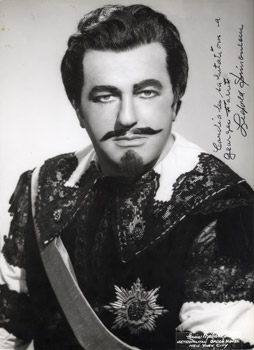

About Russell Oberlin I must add that I consider him to be the technical ideal in countertenor singing. He was also a deeply expressive singer with an instantly recognizable vocal timbre. I first encountered his voice as a young child singing The Cherry Tree Carol on the Robert Shaw Chorale’s album of holiday music. I was enchanted by what I thought the most beautiful, deep woman’s voice I had ever heard. I don’t know how my mother knew this, but she told me that this magical voice belonged to a man. I am sure that this tidbit of information lodged itself into my little noggin and became the kernel that eventually led to me pursuing a career as a countertenor. Years later I was able to share this story with Russell, who was very kind and supportive to me when I was actively building my career. You can listen to him in anything from Medieval music to lute song to Purcell to Monteverdi to Bach to Handel to Lieder to contemporary music and come away enriched and edified. In the accompanying photo he is costumed as Oberon in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a role he sang at the Covent Garden premiere of the opera in 1961. There is a live recording of his Oberon, but unfortunately it is not currently available online. Enjoy the links I’ve posted!

Così fan tutte. Nicholas mentioned a performance he undertook of the role of Ferrando in this opera which was his final stand as a tenor. One can perhaps understand this for, as he mentions, this is one of the most challenging Mozart tenor roles out there. Just for fun, I thought I would post a few recordings of “Un’ aura amorosa,” Ferrando’s principal aria. Rest assured that you will be hearing the best of the best, whichever of these singers you choose to sample!

Fritz Wunderlich (Fritz sings it here in German, as was the custom in German houses at the time. Hence, “Der Odem der Liebe.”) The most aptly named singer of all time and here, as so often, on the borderline of perfection.

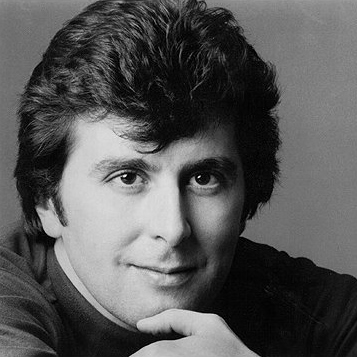

Francisco Araiza. I heard the Mexican tenor sing Tamino in Zauberflöte in Chicago in 1986 I thought I was hearing the reincarnation of Fritz. Sweetness and strength and depth of expression: he was a near-ideal Mozart tenor.

Jerry Hadley. I can’t say too much about my friend Jerry here; I’ll get too choked up. When I was in school at the University of Illinois, he was upheld as the school’s big success story. Years later, I met him when he was dating one of my best friends and we became very close friends. He also worked with me on some of his roles (Pinkerton, Cavaradossi, and Riccardo in Ballo in particular). In those coachings he taught me more than I could ever have taught me. I treasure his memory.

Alfredo Kraus. Here is the great Spanish tenor in 1990 at the age of 63 still singing circles around tenors half his age. Though his timbre is not immediately ingratiating, his taste, technique, and class carry the day.

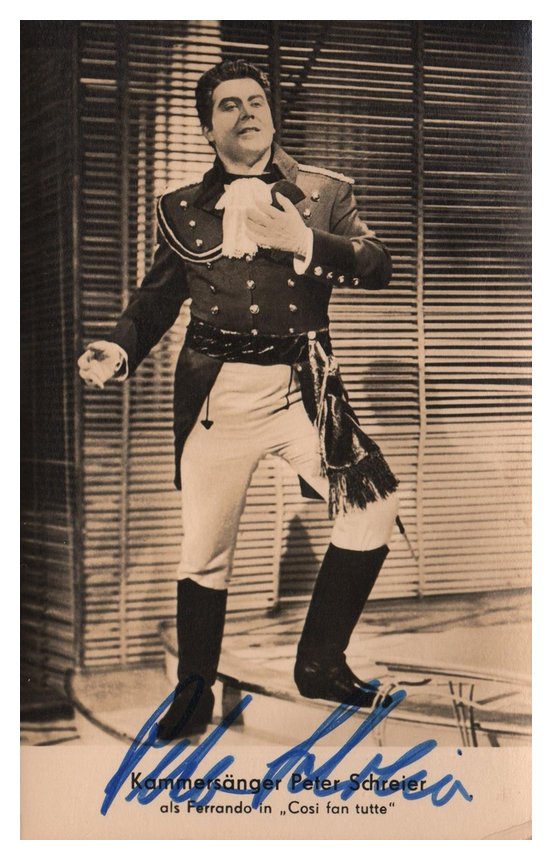

Peter Schreier. After Wunderlich’s tragic death in 1966, Peter Schreier, a young up-and-coming fellow German tenor, was called in to “fill his shoes.” Like Kraus, however, Schreier never had the beautiful vocal timbre of his predecessor. What he did have, however, in even greater profusion than Fritz, was a profound musical sensibility that moves me deeply. Check out this exquisitely-phrased 1968 recording and see if you agree.

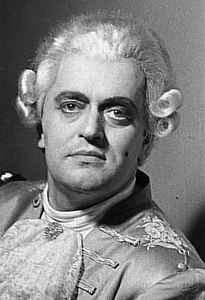

Anton Dermota. The Slovenian tenor was a staple of the Wiener Staatsoper in particular. His voice has slightly more character and edge than the previous two examples, but he also is possessed of a supreme musicality that matches both Kraus and Schreier. He has always been a favorite of mine ever since I first encountered him as Tamino in Karajan’s recording of Zauberflöte ; I hear enormous humanity in his sound.

Léopold Simoneau. The French-Canadian is perhaps the most modest-voiced of the examples given, but I am not going to dismiss him from the pantheon of Great Mozart Tenors. For while it may be true that there’s not a lot of depth in his tone, he also possesses (to my ear) the sweetest tone of anyone here presented. Besides which, his recording of Duparc songs was my first introduction to that composer, so his sound and artistry occupy a special place in my heart.

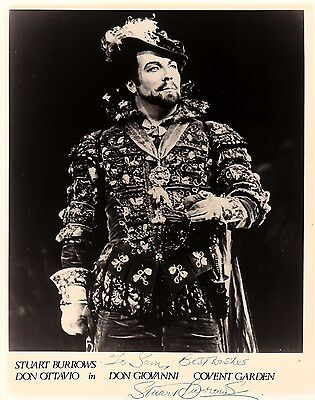

Stuart Burrows. Yet another great Welsh singer, to be placed in that great pantheon alongside the aforementioned Richard Lewis and [sometimes] Gwyneth Jones, as well as two other particularly favorites of mine, Margaret Price and Helen Watts. His timbre catches me by surprise: there is a distinctive tang that pleases me enormously. In his prime during the 1970s and 1980s he was numbered among the great Mozart tenors.

Aksel Schiøtz. Never a perfect singer, yet still a favorite of mine, the Danish tenor-turned-baritone was one of the great Lieder singers of his time. When I was a kid, I had a record of him singing Carl Nielsen songs that found an easy place in my ear and heart. His is a more quicksilver, playful approach to this aria which I like very much.

Heddle Nash. This recording is of critical historical importance. In 1935 the German conductor Fritz Busch continued his survey of Mozart operas at the newly-formed Glyndebourne festival. The previous year he had recorded Le nozze di Figaro with a distinguished cast; the following year came a more-or-less complete Così followed in 1936 by Don Giovanni. The volcanic Native American soprano Ina Souez as Fiordiligi was joined by others, including the delicious Luise Helletsgruber as Dorabella, Willi Domgraf-Fassbaender (father of the great Brigitte!) as Guglielmo, and the British tenor Heddle Nash as Ferrando. Though his voice runs out of steam in the lower range, his is still a beautiful performance.

Georges Thill. No, the great French dramatic tenor was not a Mozart singer! He is mentioned in the course of the interview (by me!) as one of the great technical masters of tenor singing. I will certainly be devoting more time to him in future episodes. For now, just let yourself bask in the beauty of his performance of Bannis la crainte et les alarmes from Gluck’s Armide. (And just cuz I love you all so much, take a gander at this newsreel clip of Thill rehearsing with the composer Joseph Canteloube (of Chants d’Auvergne fame) for the premiere of his opera Vercingétorix .

Alissa Grimaldi. Nicholas’s beloved and trusted teacher, who saw him through his transition into countertenordom and who continues to guide him.

So wonderful to listen to you two discussing singing, rep, acting, all of it! And such lovely singing from both of you.

A comment on the 18th approach to stage performance: the position of performers on the stage was as informed by the stage lighting of the day as it was by any other beliefs (or desires) for performance. Much of what we call “realism” today developed in the 19th century with limelight, gaslight and finally electric light. (This isn’t the whole story of “realism” by any means, but a significant delineation between older and more modern stage practice). In Handel’s day, performers had to know exactly where the good light was, and staging reflected the expectations of both the performers and the audience to see and be seen according to their rank and importance.

Both you and Tamagno speak very engagingly on how singing opera requires such attention to style!

Thank you so much, Donald, both for the compliments and for the fascinating comment. It seems like “finding one’s light” did not originate with Marlene Dietrich!