Episode 8. Williams & Williams

SOCIAL SHARE

SUBSCRIPTION PLATFORM

As a supplement to the first part of my interview last week with Janet Williams, I offer a cache of rare studio recordings by Camilla Williams, supplemented by live material sung by Janet Williams from the artist’s private archives. Among other material featured are excerpts from Camilla’s rarely-heard album of spirituals on the MGM Records label, and a concert given by Janet Williams in her home town of Detroit in 1989, capped by a stunning rendition of Undine Smith Moore’s arrangement of the spiritual “Watch and Pray,” dedicated to Camilla Williams.

RECORDINGS HEARD IN THIS EPISODE

CAMILLA WILLIAMS

George Gershwin: Summertime (Porgy and Bess). Camilla Williams with Al Goodman and His Orchestra and The Guild Choristers. RCA Victor 46-0004-B, 1947.

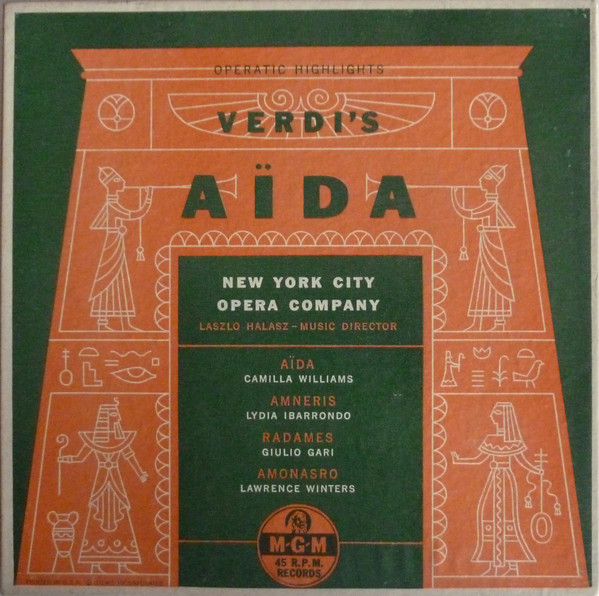

Giuseppe Verdi: Ciel, mio padre! Camilla Williams, Aida; Lawrence Winters, Amonasro (from Aida excerpts, MGM Records, K81, ca. 1951). László Halasz conducts the New York City Opera Orchestra. Additional cast includes Giulio Gari, Radames; and Lydia Ibarrondo, Amneris. (This duet is unavailable on YouTube; click here to hear Camilla’s performance of Ritorna vincitor from this recording.)

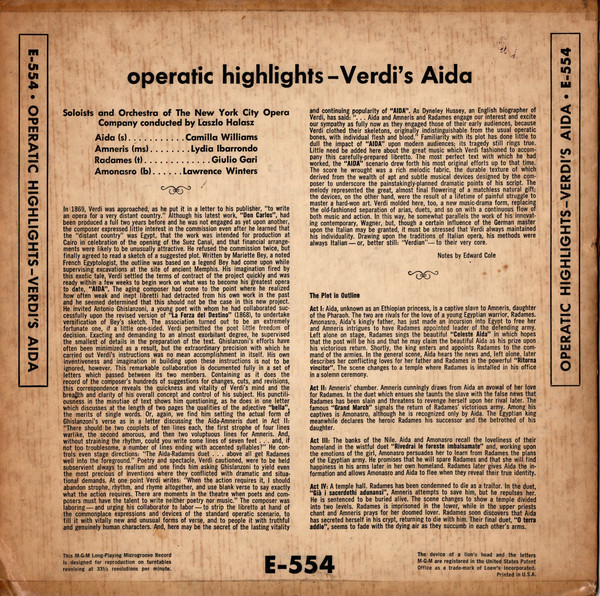

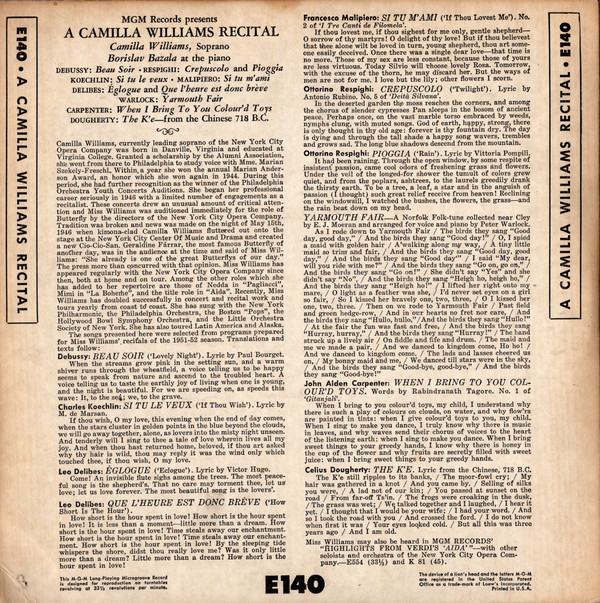

From A Camilla Williams Recital (MGM Records E140, 1952) (Borislav Bazala, pianist)

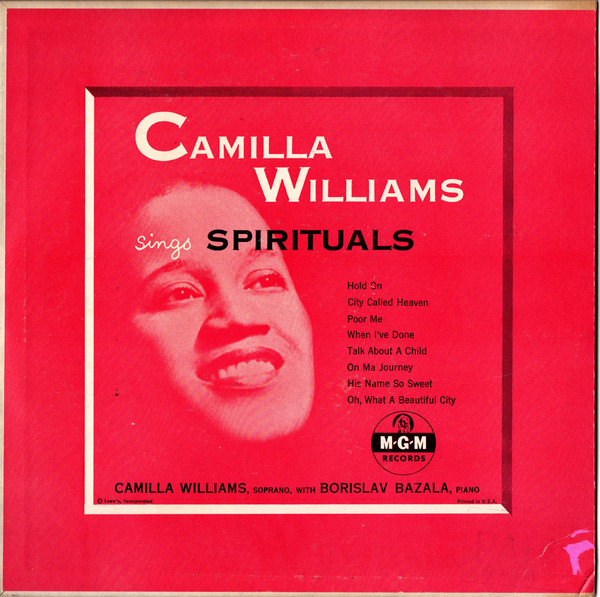

From Camilla Williams Sings Spirituals (MGM Records E-156, ca. 1953) (Borislav Bazala, pianist)

Poor Me (Trouble Will Bury Me Down)

Hold On

When I’ve Done

Oh, What a Beautiful City

The good news for intrepid collectors is that all of the above recordings are available to customers in the United States via special order. Please contact me privately either here or through my Facebook page for details.

JANET WILLIAMS RECORDINGS

Photo by Monika Rittershaus.

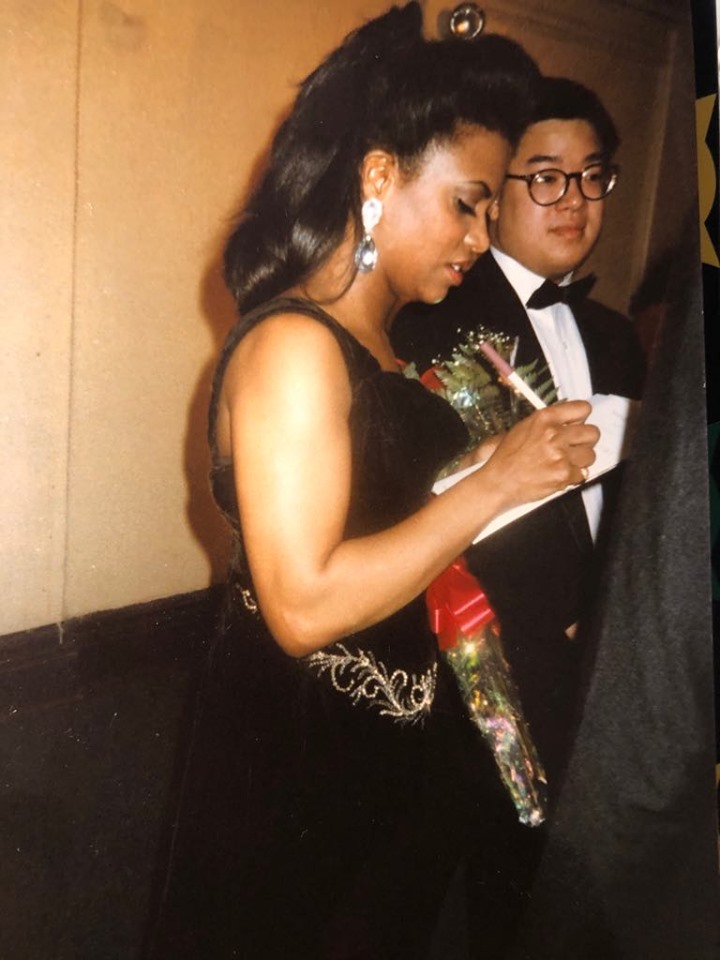

The majority of the recordings of Janet used here come from a recording of a live recital that Janet gave in her hometown of Detroit in January, 1989. She relates the story behind this recital in the next portion of our interview (which, if all goes according to plan, will be posted next week.) Her pianist is Lawrence Gee (with whom she is pictured below after the concert).

Meanwhile, here are the details of the excerpts used in this podcast episode:

Jules Massenet: Obéissons quand leur voix appelle (Manon)

Franz Schubert: Der Hirt auf dem Felsen (with Stephen Millen, clarinettist)

Spiritual (arr. Undine Smith Moore): Watch and Pray. The dedication to this piece reads, “For my dear Camilla Williams with love and pride in her career.”

Spiritual (arr. Hall Johnson): Ride On, King Jesus

Additional recordings of Janet Williams used in this episode include:

Georges Bizet: Comme autrefois (Les pêcheurs de perles) (László Halasz conducts; Janet told me this was a recording made in Budapest).

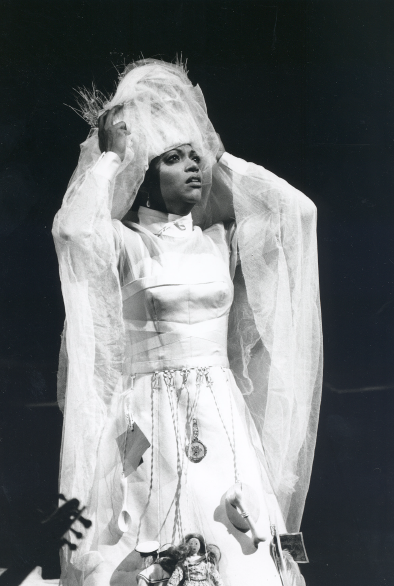

George Frideric Handel: Two excerpts from Semele (televised production from the Berliner Staatsoper) Myself I Shall Adore; and O Sleep, Why Dost Thou Leave Me?

A SLIGHT DIVERSION: CELIUS DOUGHERTY, NINA KOSHETZ, AND POVLA FRIJSH

I mentioned in passing the distinguished accompanist and composer Celius Dougherty (1902-1986). (Camilla sings his song The K’e on the podcast.) He is mostly remembered today for novelty songs such as Love in the Dictionary, although a volume of his art songs and another of his folk song settings and sea chanty arrangements have been recently been republished by G. Schirmer.

As an accompanist, probably his most important recordings are a series of Rachmaninov songs made with soprano Nina Koshetz. These are particularly significant because during her years in Russia, Koshetz and Rachmaninov had toured together (evidently the only such singer with whom he did so). I hope to do a program on the fascinating Koshetz in the near future.

On the podcast I also mentioned the deeply expressive but modest vocal talent of the singer Povla Frijsh. She and Dougherty also made a series of distinguished recordings together but, shockingly, only one of them seems to be available on YouTube: a setting of Randall Thompson’s Velvet Shoes that Dougherty and Frijsh recorded for RCA Victor in 1940. The recording gives one the opportunity to hear the curiously moving way that Frijsh had with even the simplest material. It might be an interesting endeavor to do a podcast on these three artists together. We shall see… Meanwhile, check out this fascinating radio interview with Frijsh from 1953 on the preparation and interpretation of song repertoire.

BTW, here’s a review I found of a 1936 recital that Frijsh and Dougherty did at Town Hall on November 21 of that year:

The New York Times, Sunday November 22, 1936/Music in Review by Olin Downes/Povla Frijsh, Danish Soprano, Is Heard at Town Hall

The art of song interpretation in its highest estate was enjoyed by the large audience which gathered in Town Hall last night for the recital given by Povla Frijsh, the Danish soprano. There was a big ovation for the singer when she first appeared and, had she been so minded, she might have doubled the length of the program, so insistent was the applause after each of her selections.

To judge the work of this great interpreter from the purely vocal point of view would result in a misunderstanding of her status as an artist. For the text is basic in every phrase she sets forth and is the primary factor in the coloring and nuance of the tones as they fall into their appointed place in the general scheme. Naturally, this is the goal for which all singers strive. But how pitifully few attain it to anything like the degree made known in Miss Frijsh’s extraordinary evocations of innumerable contrasting moods at this recital.

As always her list of offerings was a model of program-making and contained numerous little-known contributions as well as more familiar items. For her opening song, Miss Frijsh had chosen Bach’s “Bist du bei mir,” which was remarkable for its tenderness and depth of devotion, and strikingly juxtaposed, Schubert’s delicated lied, “Der Schmetterling,” followed hard upon it. This latter offering was given with such gossamer lightness of pianissimo in the expert delineation of its joyous measures that it had to be repeated.

Miss Frijsh was a trifle hoarse and this interfered with the steadiness of some of her tones in her gripping interpretation of the next Schubert song, “Death and the Maiden.” There was almost no attempt to make the violent and melodramatic difference of tone quality between the two protagonists in this lyric so frequently indulged in. But the simplicity and directness with which she expressed the awe-struck timidity and fear of the maiden and the profoundly consolatory response were equally touching and impressive. As fine, in its way, was the way the third Schubert number, “Erstarrung,” with its deeply felt mood of anguish and despair.

In the French group, next attempted, Miss Frijsh rose to her greatest heights in a superb reading of Fevrier’s “L’Intruse,” which was a little masterpiece of dramatic power and beyond praise in the establishing of an all-enveloping atmosphere of haunting mystery. Biting satire was so cleverly handled in another of the Gallic songs, Poulenc’s “1904,” that it bore repetition, and exotic sensuousness was most compellingly encompassed in the succeeding “Les roses d’Ispahan” of Fauré.

Arrived at the third group, comprising German lieder by Trunck (sic), Buesser and Marx and children’s songs by Fiona McCleary and Kricka. Miss Frijsh’s voice overcame the huskiness which sometimes handicapped her singing earlier in the evening, her tones being particularly fresh and free in Trunck’s “Die Stadt.” Kricka’s “Die unfolgsamen Zicklein” served to demonstrate the artist’s fund of sly humor in a schedule which ran the whole gamut of human emotions. The list also comprised numbers by Grieg and Fini Henriques, sung in the original language. Celius Dougherty, at the piano, provided accompaniments worthy of Miss Frijsh’s splendid art.

In next week’s episode, Janet speaks more about Camilla; we relive our memorable time spent with the San Francisco Opera; and Janet reveals how she went to study in Paris with Régine Crespin and ended up as a member of the ensemble of the Berliner Staatsoper, ultimately settling here in Berlin with her husband, the distinguished German director and stage designer Fred Berndt.